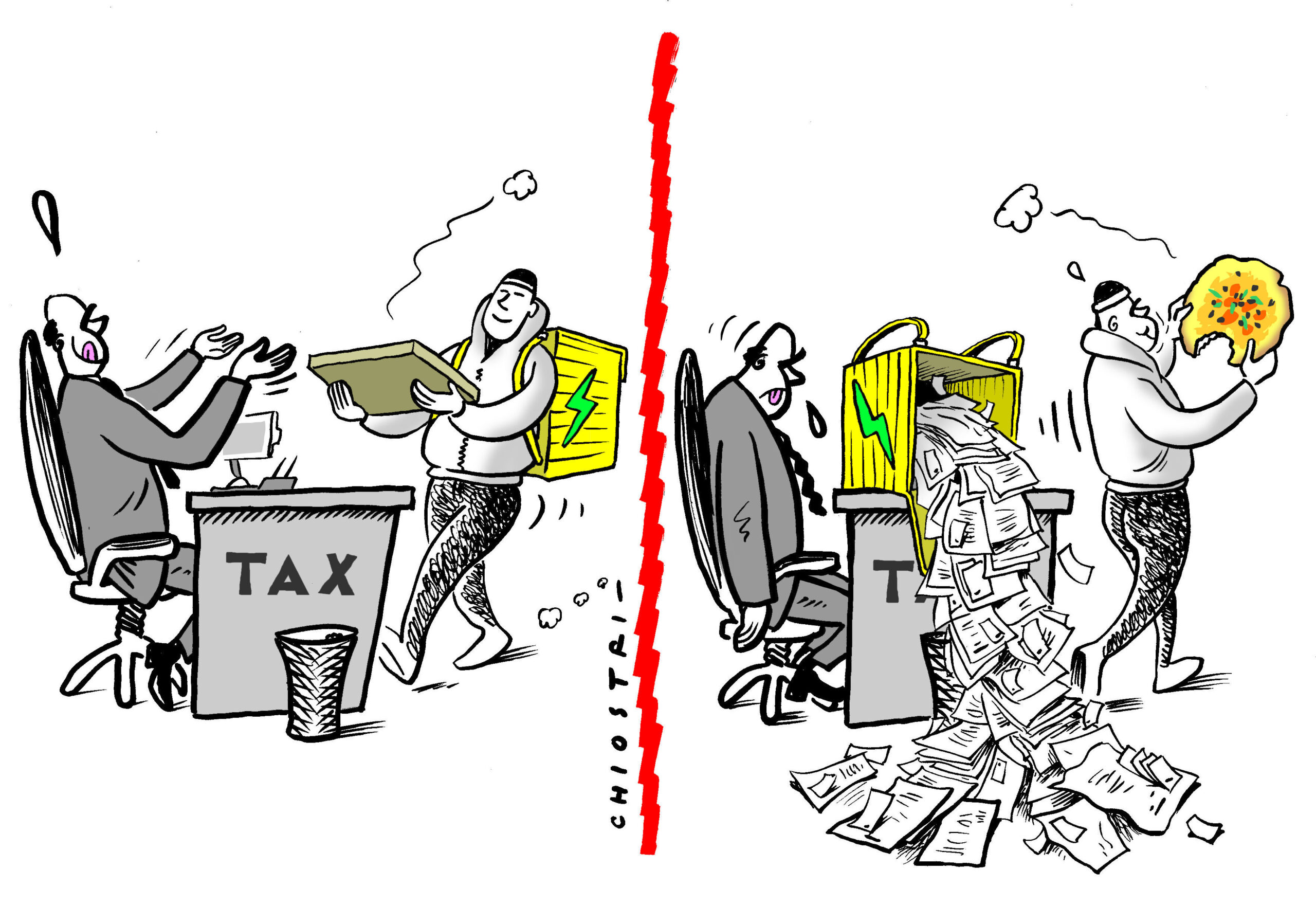

On 15 July 2020, the European Commission (EU Commission) unveiled a Proposal for a Council Directive amending Directive 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation (the so-called ‘DAC 7’), which seeks to improve the existing framework for exchange of information in the field of direct taxation within the EU, by introducing, inter alia [1], rules on reporting of tax information by multisided digital platforms [2]. The declared intention behind the initiative is, on the one hand, to ensure a level playing field for competition within the EU by targeting income underreporting by platform sellers and, on the other hand, to minimise administrative and compliance costs for platform operators due to the EU Member States imposing unilateral reporting obligations on those digital players [3].

The latest draft of the DAC 7 proposal was discussed among the Permanent Representatives Committee inside the Council of the European Union (EU Council) on 25 November 2020 and received formal endorsement by the Economic and Financial Affairs Council of the EU (ECOFIN) in a videoconference on 1 December 2020.

The sixth amendment to the current EU Directive on Administration Cooperation (DAC) in the field of direct taxation in less than a decade – which the EU Council is expected to adopt, in the last agreed draft, in the coming weeks – provides for a new set of rules for automatic exchange of information on income earned by sellers on sharing and gig economy platforms, as from 1 January 2023 onwards.

The EU proposal does not come in ‘splendid isolation’ since, on 3 June 2020, after a public consultation held in February-March of this year 2020, the OECD finalized its Report on ‘Model Rules for Reporting by Platform Operators with respect to Sellers in the Sharing and Gig Economy’, which also lays down a series of obligations for sharing and gig economy platforms to collect information on income made by users on their online marketplaces and to report that information to tax authorities.

In a forthcoming (amazing the speed at which today’s changes are unfolding…) article soon available in Kluwer’s EC Tax Review (Issue 1 – 2021), I draw a tentative comparison of the initiatives developed in parallel by the EU and the OECD, highlighting similarities and differences existing between the two. In this blog, I will rather focus on some elements of the DAC 7 proposal that you might not find in the EC Tax Review’s article since they have been introduced only at a later stage, within the latest draft of the EU proposal as agreed upon by the EU Council in late November.

Closer to the OECD, But the EU Has the Lead

Many of the amendments introduced in the DAC 7 proposal, in its latest draft text, are made to take account of the parallel initiative by the OECD in the field, so that the two instruments come closer to one another. On this point, the EU proposal even maintains that, by adopting the new rules on reporting of tax information by platform sellers as framed by the OECD, ‘non-Union jurisdictions will have sufficient incentives to follow the leading example of the Union and implement the collection and mutual automatic exchange of such information on reportable sellers according to the [OECD] Model Rules’ [4].

Coming down to the details of the DAC 7 proposal, as it often occurs when new rules are set to be introduced, it all starts with ‘definitions’ laying down the subjective, objective and territorial scope of the legislative initiative.

As for the subjective scope, a key definitional term is, obviously, that of ‘platform’, which is defined broadly and with nearly an identical language under the EU and OECD initiatives, i.e. as ‘any software, including a website or a part thereof and applications, including mobile applications, accessible by users and allowing Sellers to be connected to other users for purpose of carrying out a Relevant Activity, directly or indirectly, to such users’. On equal terms under the EU and OECD initiatives, an exclusion is provided for platforms that only (i.e. without any further intervention) allow: (i) processing of payments in relation to Relevant Activity; (ii) users to list or advertise a Relevant Activity; or (iii) redirecting or transferring of users to a Platform [5]. However, permanent establishment (PE) of non-EU platforms within the EU and, further, non-EU platforms facilitating relevant activities in an EU Member State are also within the scope of the DAC 7 proposal, both circumstances which do not occur under the OECD Model Rules [6].

As regards the objective scope, the key definition lies in the kinds of sharing and gig economy activities subject to tax information reporting. Rentals of immovable property [7] and the provision of personal services by platform sellers are both reportable activities under the EU and the OECD initiatives [8]. However, the DAC 7 proposal broadens the scope of tax information reporting to other activities such as the sale of goods and the rental of any mode of transport (a further expansion to investment- and lending-based crowdfunding was instead deleted from the latest version of the EU proposal) [9].

The inclusion of the sale of goods as a ‘Relevant Activity’ under the DAC 7 proposal will likely have a far-reaching impact as it brings more platform sellers into the scope of tax information reporting (e.g. sellers on well-known platforms such as Amazon, e-Bay, Etsy, or even Facebook, which has its own marketplace). In this connection, the exclusion from tax information reporting by platforms for users making less than 30 sales of goods on a platform and in return for an overall consideration of less than EUR 2,000 per year provides only a de-minimis exemption which, in my view, will help neither dramatically reduce the number of reportable sellers nor effectively monitor the thresholds not being exceeded [10]. Further issues might arise with the concept of ‘goods’ which, although defined straightforwardly as ‘any tangible property’ under the last version of the DAC 7 proposal, does not come clear in case of transactions where elements of both goods and services are involved [11].

© 2020 Kluwer Law International B.V., all rights reserved.

The DAC 7 proposal casts a wide net in terms of territorial scope. In fact, sellers either having a primary address, a tax identification number (TIN), or, for entities, a PE in an EU Member State, are all considered as EU residents and therefore subject to tax information reporting. Tax information on sellers, whether resident or not, who rent out immovable property located in an EU Member State must also be reported by platforms [12]. Importantly, as similarly provided under the OECD Model Rules, for reasons of competition neutrality, compliance efficiency and administrative simplification, reporting obligations by platforms are meant to cover both cross-border and domestic activities [13].

Qualified Non-Union Platform Operators and Automatic Exchange of Equivalent Information

The main novelty introduced in the latest draft of the DAC7 proposal however relates to the setting-up of coordination mechanisms for tax information reporting between EU and non-EU countries. Notably, the DAC 7 proposal provides that, in order to reduce administrative and compliance burden relating to tax information reporting by a platform that is neither resident nor established within the EU, the foreign platform – named ‘Qualified Non-Union Platform Operator’ – must be relieved from an obligation to report tax information to an EU Member State if ‘equivalent information’ is exchanged under an agreement between a non-EU country and an EU Member State (i.e. ‘Effective Qualifying Competent Authority Agreement’). In such an event, the information will be provided to the tax administrations of the EU Member States directly by the non-EU country’s tax administration ‘(i.e. ‘Qualified Non-Union Jurisdiction’) [14].

However, relief from tax information reporting for a Qualified Non-Union Platform Operator applies only to the extent that: (i) the information received by an EU Member State under the agreement with a non-EU country relates to the activities in the scope of the DAC 7 proposal (i.e. ‘Qualified Relevant Activities’); (ii) the information exchanged under the agreement with a non-EU country is equivalent to the information exchanged by platforms under the DAC 7 proposal [15]; and (iii) the tax authorities of a non-EU country ensure effective implementation of reporting and due diligence obligations [16].

Equivalence in terms of tax information exchanged under an agreement between a non-EU country and an EU Member State [17] is a condition to be determined through implementing acts by the EU Commission [18], which, for this purpose, must however take account of a series of parameters, and in particular: (i) the definitions of Reporting Platform Operator, Reportable Seller, Relevant Activity; (ii) the procedures applicable for the purpose of identifying Reportable Sellers; (iii) the reporting requirements; and (iv) the rules and administrative procedures that non-Union jurisdictions shall have in place to ensure effective implementation of, and compliance with, the reporting and due diligence procedures set out in that regime.

These latest developments as regards the concepts of Qualified Non-Union Platform Operators and Automatic Exchange of Equivalent Information are certainly welcome, given their aim to avoid multiple reporting of tax information by platforms. However, there might be some hindrances in their application. A first concern relates to the discretionary powers conferred to the EU Commission under the DAC 7 proposal in terms of assessing whether the information exchanged with a non-EU country is ‘equivalent’ or not. A second element to consider relates to the fact that, as explained, the scope of information tax reporting under the OECD Model Rules, which might be used as a framework by non-EU jurisdictions to develop their own tax information reporting obligations for platforms, is narrower than as provided under the DAC 7 proposal. Thus, it might occur that an activity such as the sale of goods, which needs to be reported based on the DAC 7 proposal, is not instead subject to tax information reporting in a non-EU country, so that registration in an EU Member State by a non-EU platform is required. Third, the criterion of ‘equivalent information’ is not subordinated to the fact that a non-EU country also considers the information exchanged under the DAC 7 as ‘equivalent’ for its own tax information reporting obligations, which means that EU platforms might not be relieved from reporting of tax information for activities carried out in a non-EU country as instead non-EU platforms can be for activities within the EU. This element might be detrimental for EU platforms to compete with non-EU platforms on a level playing field worldwide.

Conclusions

The initiatives launched in parallel by the EU and the OECD, laying down a new set of rules for tax information reporting by sharing and gig economy platforms, show the pivotal role assumed by multisided digital platforms at present. Indeed, the prominent role of those platforms within the supply chain makes them ideally positioned to become the addressees of new tax obligations against underreporting of income by users. This implies, however, a single set of rules or at least coordinated standards across different jurisdictions. Although mirroring one another in several respects, the EU and OECD initiatives are not perfectly aligned and the mechanisms of coordination between the two instruments envisaged so far might not be adequate and thus fall short of their ultimate intention.

[1] Other relevant fields where the DAC 7 proposal introduces amendments to the current Directive 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation relate to the notion of foreseeably relevant information, group requests for information, joint audits and data security breaches.

[2] Although concerning administrative cooperation in the field of direct taxation, the DAC 7 proposal clarifies that the information exchanged may also be used for assessment, administration and enforcement of VAT and other indirect taxes. Use of the information exchanged for other purposes is instead subject to permission by the EU Member State providing the information.

[3] See Commission Staff Working Document Impact Assessment Tax Fraud and Evasion – Better Cooperation between National Tax Authorities on Exchanging Information Accompanying the Document Proposal for a Council Directive amending Directive 2011/16/EU on Administrative Cooperation in the Field of Taxation, SWD(2020) 131 final (15 July 2020), p. 5.

[4] See Whereas 13b of the DAC 7 proposal.

[5] See Annex V, Section I(A)(1) of the DAC 7 proposal.

[6] See Annex V, Section I(A)(4)(a)(iii) and (b) of the DAC 7 proposal. Notably, a platform that is not established in the territory of any EU Member State must register with the competent authority of any EU Member State upon commencement of its activity within the EU. Penalties – to be determined by each EU Member State independently but in a way to be ‘effective, proportionate and dissuasive’ (see Article 25a of the DAC 7 proposal) – may apply, as well as other measures to enforce compliance, in case of a platform failing to register itself. Upon cessation of its activities, de-registration is also possible (as well as re-registration after it). Contrary to the original EU proposal, no relevance in the last version of the DAC 7 proposal is instead attached to registration by a non-EU platform for VAT purposes.

[7] As framed by Annex V, Section I(A)(5)(a) of the DAC 7 proposal, the concept of immovable property encompasses ‘both residential and commercial property, as well as any other immovable property and parking spaces’.

[8] Under both the EU and OECD initiatives, carve-outs are provided for platform sellers that are governmental bodies, for entities whose stock are regularly traded on an established securities market, for large hotel chains or tour operators, as well as for sellers acting as employees of a platform.

[9] See Annex V, Section I(A)(5)(c) and (d) of the DAC 7 proposal.

[10] See Annex V, Section I(B)(4)(d) of the DAC 7 proposal, and also taking into account the wording of Whereas 14a, which stipulates that ‘in order to avoid the risk of circumventing reporting obligations by intermediaries appearing on the platforms as a single seller while managing a large number of property units, appropriate safeguards should be designed’.

[11] See Annex V, Section I(C)(9) of the DAC 7 proposal. A methodology for drawing a distinction between elements of goods and services within a bundled transaction is instead provided under the OECD Model Rules.

[12] See Article 8ac(2) and Annex V, Section II(D) of the DAC 7 proposal.

[13] See Whereas 9a of the DAC 7 proposal.

[14] See Annex V, Section I(A)(4a)(4b) and (4c) of the proposed DAC 7. In this connection, however, there is a lack of clarity as regards between which countries an ‘Effective Qualifying Competent Authority Agreement’ must be in place. Notably, Point 4c above requires that an agreement for automatic exchange of information exists between ‘competent authorities of a Member State and a non-Union Jurisdiction’, whereas Point 4b above stipulates that a ‘Qualified Non-Union Jurisdiction’ is regarded as such if it ‘has in effect an Effective Qualifying Competent Authority Agreement with the competent authorities of all Member States, which are identified as reportable jurisdictions in a list published by the non-Union jurisdiction’ (emphases added). It also unclear whether the equivalent information must necessarily be reported by the non-EU country in which the foreign platform is resident (as it appears from a reading of Point 4a above) or if, instead, it suffices that the information is obtained by an EU Member State as a result of an agreement with any other non-EU country (e.g. the non-EU country where a foreign platform has a PE if such non-EU country requires ‘equivalent’ tax information reporting by the PE).

[15] See Whereas 13a of the DAC 7 proposal.

[16] See Whereas 16 of the DAC 7 proposal.

[17] As specified in Whereas 13c of the DAC 7 proposal, any (automatic?) exchange of information agreement, based on either a bilateral or a multilateral instrument, is considered for this purpose. Other than by its own initiative, the Commission’s action can also be triggered by a request from an EU Member State, also in advance of an envisaged conclusion of an agreement for exchange of information with a non-EU country.

[18] EU Commission’s exercise of implementing powers will however be subject to control by EU Member States, in accordance with Regulation (EU) no. 182/2011.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer International Tax Blog, please subscribe here.