Recently, national courts of several EU member States (notably France[1], Italy[2], the Netherlands[3] and Spain[4]) referred to the landmark judgments of the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) in the so-called “Danish cases”.[5] On 20 April 2020, the Swiss Supreme Court gave its own interpretation of these judgments[6] in an outbound dividend case involving art. 15(1) of the Swiss-EU Savings Agreement[7] which provides an exemption comparable to that of art. 5 of the Parent-Subsidiary Directive (PSD). While the reference to EU case law for purposes of interpreting this provision is to be fully approved, the Swiss judgment however deserves some critical remarks.

Facts of the case

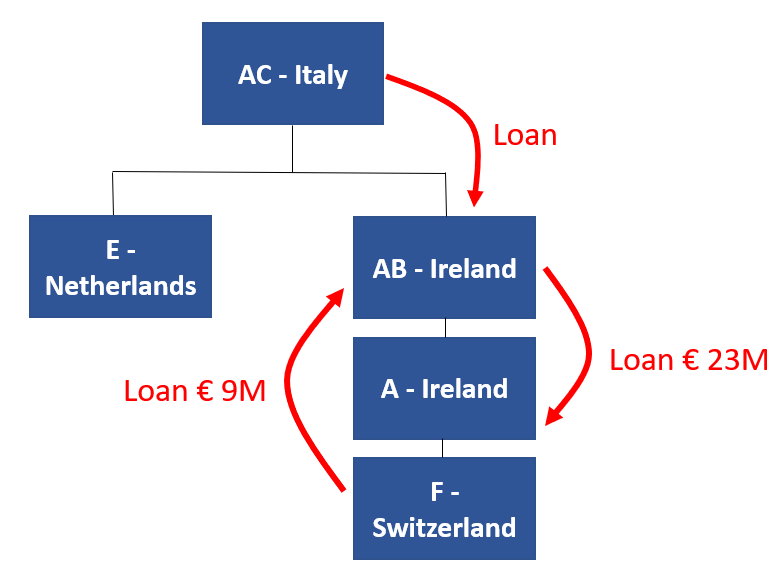

Historically, a Swiss company (F) was owned by a parent company established in the Netherlands (E) Dividends distributed by F to E (1999-2003) had been subject to a 15% withholding tax (instead of the nil rate applicable under the Switzerland-Netherlands tax treaty) on the ground that F had initially been owned by a Netherlands Antilles company and had been found to have been abusively transferred to E. Between 2005 and 2006, an Irish affiliated company (A) acquired F from E together with the latter’s intellectual property rights and R&D costs. These acquisitions had been financed by a loan granted by A’s parent company (AB), also an Irish corporation. On the facts, F had substantial liquid assets with corresponding distributable reserves upon its transfer to its Irish company. The restructuring thus entailed a significant reduction of the latent withholding tax liability on these reserves (ie from 15% to 0% due the possible benefit of the Swiss-EU Agreement). In 2007, F made a dividend distribution (CHF 14 million) on which it paid, in 2011, the standard 35% Swiss withholding tax. It is also relevant that the Irish companies were ultimately owned by a EU parent company, in Italy.

Figure: corporate structure before the dividend distribution (2007).

Issue at Stake and Decision of the Lower Court

A (Ireland) sought to rely on art. 15(1) of the Swiss-EU Agreement to claim a full refund of the Swiss withholding tax on the 2007 dividend distribution. This provision aims at providing an exemption comparable to that of art. 5 of the Parent-Subsidiary Directive (PSD). Similarly to art. 1(4) PSD, art. 15(1) of the Swiss-EU Agreement reserved “the application of domestic or agreement-based provisions for the prevention of fraud or abuse in Switzerland and in Member States”. However, art. 15 does not contain the GAAR introduced in art. 1(2) PSD in 2015.

In 2018, the Lower Court (Federal Administrative Court) ruled against the taxpayer but did not consider the abusive nature of the restructuring.[8] Rather, the Lower Court treated the case at hand as a conduit situation and considered that art. 15(1) was subject to a beneficial ownership limitation. For the court, this limitation was not satisfied because the board of directors of the Irish company was composed of the same individuals as its parent company’s board. Clearly, this fact alone (a common business practice) is not sufficient to deny beneficial ownership to an intermediary.[9] The Lower Court’s reasoning consisting in reading beneficial ownership into art. 15(1) resembles the one adopted recently by the French Conseil d’État in relation to art. 5 PSD. However, the denial of the benefit of art. 15(1) despite the fact that all the involved parties involved were EU residents and potentially entitled to the same benefits is clearly incorrect, whether one relies on the OECD Commentary[10] or the CJEU judgments in the Danish cases.[11]

Decision of the Swiss Supreme Court

On appeal, the Swiss Supreme Court confirmed the Lower Court’s decision but instead focused on the restructuring having entailed a reduction of the Swiss withholding tax latent liability. The existence of abuse was upheld due to (i) the temporal connection between the share transfer (2006) and the distribution in 2007 of pre-acquisition reserves and (ii) the fact that the Irish company did not have employees or premises of its own. In our opinion, the first criterion (temporal connection) was here decisive.[12]

On the other hand, the existence of a mere holding activity (as opposed to a commercial) is per se not sufficient to uphold the existence of an artificial arrangement.[13] More fundamentally, the Supreme Court made important observations as regards the relevance of the CJEU’s case law in the context of the Swiss-EU Agreement.

Principle of Common Interpretation and Reliance on the CJEU ‘Danish’ Decisions

The Supreme Court rightly held that the interpretation of art. 15 of the Swiss-EU Agreement was subject to the customary rules of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT).[14] The Court was equally right in holding that the principle of common interpretation dictates that the CJEU’s case law be referred to in the context of art. 15. The Supreme Court’s references to EU case law remained however confined to the Danish cases.[15] While certainly relevant as a matter of principle, these cases however dealt with conduit situations in which the beneficial owners were not EU residents. By contrast, the case at hand involved EU resident companies, and following the Supreme Court’s approach, an abusive restructuring as opposed to a conduit case.

On the Existence of an Implied Beneficial Ownership Limitation

The question of whether art. 15(1) of the Swiss-EU Agreement incorporates a beneficial ownership limitation was left opened as the limitation does not flow from the text of this provision and, perhaps more interestingly, because the Supreme Court considered that this issue had not been settled by the CJEU in the PSD cases (C-116/15).[16] On this point, the Swiss Supreme Court’s interpretation differs from the position of the French Conseil d’État, which instead derived a beneficial ownership limitation from the CJEU judgment in the PSD cases.[17] The Supreme Court’s approach also departs from its own case law, where it considered that the beneficial ownership limitation was implicit to the Switzerland-Denmark tax treaty.[18] Rather, the reasoning in the case commented here resembles the one followed by the Supreme Court in the A Holding ApS case which led to the recognition of an implied prohibition of abuse in Swiss tax treaty practice.[19]

On the Existence and the Notion of a General Prohibition of Abuse of Rights

The Supreme Court relied on the Danish cases to establish that art. 15 of the Swiss-EU Agreement is subject to a prohibition of abuse of rights.[20] However, the Court then went on to consider other sources,[21] namely the 2003 OECD guiding principle[22] – ie the ancestor of the 2017 Principal Purpose Test (PPT)[23] – the principle of good faith (art. 26 VCLT) and the general abuse of rights doctrine under Swiss law. There is certainly an increased convergence between the OECD standards and the CJEU’s case law.[24] An approach more coherent with the Supreme Court’s desire to achieve common interpretation would have been to refer to the constituent elements of abuse of rights mentioned in the Danish cases and flowing from the CJEU’s judgment in Emsland-Stärke (C-110/99).

In the end, however, the Court did not fully endorse the findings of the CJEU and left opened the question of whether art. 15 is subject to an autonomous prohibition of abuse rights.[25] Leaving EU law aside, we find that the Court’s reasoning is here inconsistent with its traditional reading of art. 31 and 26 VCLT following the A Holding ApS case. Moreover, if, as the court seems to suggest, the matter was in the end confined to the reservation of domestic anti-avoidance rules, we would have expected a reference to the established case law of the CJEU thereupon (inter alia Eqiom, C-6/16).

On the Consequences of Abuse

More troubling, on the other hand, is the observation made by the Supreme Court that the existence of abuse does not automatically entail a recharacterization of facts leading, as the case may be, to the granting of any treaty benefits available in the absence abuse. Rather, the Supreme Court suggested that an express provision is necessary and referred to the discretionary relief provided by art. 7(4) of the BEPS Multilateral Instrument.

This assertion is inconsistent with Swiss administrative practice to date[26] and with the principle of proportionality, which requires alternative treaty benefits to be granted on the basis of a recharacterization of facts.[27] More surprisingly, the Supreme Court left open the question of whether such a practice would be in line with art. 15 of the Swiss-EU Agreement.

We appreciate that the CJEU may have created some confusion on this point in the Danish cases.[28] However, the CJEU’s observation thereupon – rightly criticized in scholarly writing and confusing compared to AG Kokott’s clear opinion[29] – concerned the existence of abuse as well as the burden of proof and not strictly speaking the recharacterization stemming therefrom.[30] Hence, we believe that the findings of the CJEU in Halifax remain relevant to art. 15 of the Swiss-EU Agreement (ie “transactions involved in an abusive practice must be redefined so as to re-establish the situation that would have prevailed in the absence of the transactions constituting that abusive practice”),[31] particularly where a share transfer is ignored due to its abusive nature. There is therefore no doubt in our opinion that the principle of alternative relief traditionally followed by Swiss administrative practice applies (and should apply) to the Swiss-EU Agreement.

Final Remarks

The principle of common interpretation which led the Swiss Supreme Court to refer to the Danish cases for the purpose of interpreting the Swiss-EU Agreement is to be welcomed. Moreover, the Supreme Court’s reasoning which focused on an abusive restructuring is undoubtedly more convincing than the Lower Court’s approach based on beneficial ownership. Leaving aside the existence of an abusive restructuring, we fail to see how the benefit of the Swiss-EU Agreement could be denied where it is clearly established that all the companies involved are EU residents and potentially entitled to the benefit of this Agreement.

On the other hand, contrary to what the Supreme Court suggests, the existence of abuse (in particular where a share transfer is ignored) always implies a proper recharacterization and the subsequent availability of alternative benefits. On this point, the principle established in Halifax remains valid.

Finally, it is remarkable that the Swiss Supreme Court did not infer from the CJEU’s judgment (C-116-16) that art. 5 PSD was subject to a beneficial ownership limitation, while, on the other hand, the French Conseil d’État recently arrived at this conclusion. Clearly, on this point at least, the judgments of the CJEU in the Danish cases lack clarity. The debate regarding the articulation between beneficial ownership and the prohibition of abuse of rights thus continues.

[1] Conseil d’État decisions no. 423809 et al. of 5 June 2020.

[2] Corte di cassazione decision no. 14756 of 10 July 2020.

[3] Hoge Raad decision no. 18/00219 of 10 January 2020.

[4] Tribunal Económico-Administrativo Central, rec. 185/2017 and rec. 2188/2017, 8 October 2019.

[5] CJEU, Joined cases C-116/16 and joined cases C-115/16. For a critical discussion of these cases see, inter alia, L. De Broe and S. Gommers, ‘Danish Dynamite: The 26 February 2019 CJEU Judgments in the Danish Beneficial Ownership Cases’, EC Tax Review 2019/6, p. 270 et seq., A. Zalasiński, ‘The ECJ’s Decisions in the Danish “Beneficial Ownership” Cases: Impact on the Reaction to Tax Avoidance in the European Union’ (2019) 2 International Tax Studies, p. 1 et seq. and S. Bærentzen, ‘Danish Cases on the Use of Holding Companies for Cross-Border Dividends and Interest – A New Test to Disentangle Abuse from Real Economic Activity?’ (2020) 12 World Tax Journal, p. 3 et seq.

[6] Swiss Supreme Court, decision 2C_354/2018 of 20 April 2020, hereinafter ‘Commented decision’, English translation in the ITLR forthcoming.

[7] This agreement was renamed as of 1 January 2017 ‘Agreement between the Swiss Confederation and the European Union on the automatic exchange of financial account information to improve international tax compliance’. Article 15 has been renumbered (article 9) but is otherwise unmodified.

[8] Federal Administrative Court, A-7299/2016, 20 ITLR 625.

[9] R. Danon, The Beneficial Ownership Limitation in Articles 10, 11 and 12OECD Model and Conduit Companies in Pre- and Post-BEPS Tax Treaty Policy: Do We (Still) Need It? in G. Maisto (ed) Current Tax Treaty Issues: 50th Anniversary of the International Tax Group (IBFD 2020), sec. 15.2.5.6.

[10] OECD Commentary on Article 10 (2017), para. 12.7.

[11] See Joined cases C-115/16, [94]. See also Conseil d’État decisions no. 423809 and others of 5 June 2020, [4] and Société Eqiom et Société Enka, Conclusions of Rapporteur public E. Bokdam-Tognetti, p. 7. More generally for a critical assessment of the Swiss practice, see R. Danon, ‘Tax treaty abuse from a Swiss Perspective: Current state of affairs, uncertainties and future perspective’ in Au carrefour des contributions : Mélanges de droit fiscal en l’honneur de Monsieur le Juge Pascal Mollard (Stämpfli 2020), pp. 429-430

[12] Commented decision, [4.4.4].

[13] See for example joined Cases C‑504/16 and C‑613/16, [72] and [73].

[14] Commented decision, [3.1]

[15] Ibid., [3.4.1] and [3.4.2].

[16] Ibid., [3.4.3].

[17] Société Eqiom et Société Enka, Conclusions of Rapporteur public E. Bokdam-Tognetti, pp. 2-3.

[18] Swaps case, 18 ITLR 138, 2C_364/2012.

[19] 8 ITLR 536, 2A.239/2005.

[20] Commented decision, [3.4.3].

[21] Ibid., [4.3.1].

[22] See now OECD Commentary on Article 1 (2017), para. 61.

[23] Art. 29(9) 2017 OECD MC and UN MC.

[24] See Joined cases C-115/16, [127].

[25] Commented decision, [4.5.4].

[26] Federal Administrative Court, A-2744/2008; R. Danon and T. Obrist, ‘La théorie dite des «anciennes réserves» en droit fiscal international – Commentaire de l’arrêt du Tribunal administratif fédéral A-2744/2008 du 23 mars 2010’ Revue fiscale no. 9/2010, p. 621 et seq and S. Oesterhelt, ‘Altreservenpraxis, internationale Transponierung und stellvertretende Liquidation’, IFF Forum für Steuerrecht 2017/2, p. 106 et seq.

[27] R. Danon and H. Salomé, ‘The BEPS Multilateral Instrument’, IFF Forum für Steuerrecht 2017/3, 236.

[28] See eg Joined Cases C‑115/16, [108] and [120]

[29] See Opinion of AG Kokott, Case C‑117/16, [88] et seq.

[30] See De Broe and Gommers, supra n.5, pp. 284-285; p. 286 and pp. 297-298; Danon, n.9, sec. 15.2.7.2.

[31] Halifax (C-255/02), [94]; see also Cussens (C-251/16), [47].

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer International Tax Blog, please subscribe here.