Introduction

Article 11 of the VAT Directive allows EU Member States (MS) to regard as a single taxable person a group of persons established in their territory who, while legally independent, ‘are closely bound to one another by financial, economic and organisational links’. The lack of further specification about how this provision should be interpreted has pushed the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to release decisions on this matter on more than one occasion.

Skandia America (USA) (Case C-7/13) can be considered one of the most important judgements of the CJEU in the field of VAT grouping. The case deals with a non-EU company, established in the United States, that supplies services to its Swedish branch, member of a VAT group in Sweden. According to the Court’s decision, the consideration of the group as a single taxable person implies a break in the legal relationship between the Swedish fixed establishment (FE) and its non-EU (i.e. the US) head office. This ‘legal separation’ makes it impossible to consider those two entities as a single taxable person for VAT purposes, so that the services supplied from the head office to its FE – which cannot be regarded as supplied to the FE, but to the group itself – must fall within the scope of VAT. As the CJEU has recently reinstated in Kaplan International colleges UK (Case C-77/19), this conclusion is just the ultimate consequence of the single taxpayer principle on which Article 11 of the VAT Directive relies.

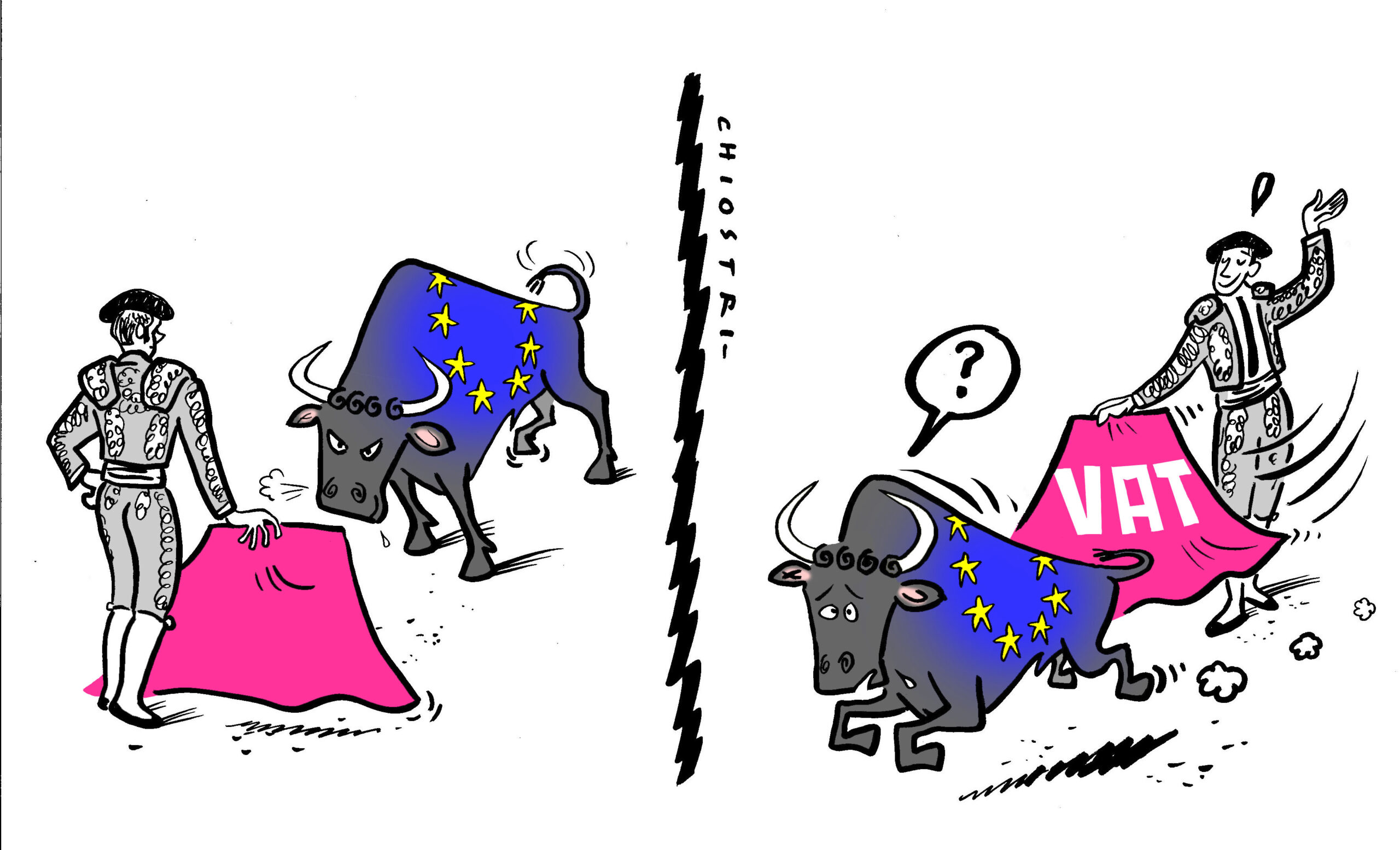

The impact of Skandia America in Spain or the need to reopen an old debate

In light of the CJEU’s decision in Skandia America, the question we pose in this article is: what would occur if the VAT grouping scheme applicable in the branch’s MS did not formally recognise the group as a single taxable person? Could we speak about a ‘legal separation’ between the FE and its head office even in this case?

The situation I am trying to describe can look weird, as VAT grouping schemes currently applicable in most MS are based on the non-chargeability of VAT to intra-group transactions. However, this is not the case with Spain, where Article 11 of the VAT Directive was implemented using a sui generis and quite a controversial technique.

In Spain, all those groups of entities who meet the requirements can opt for applying a special VAT scheme and, moreover, they can choose the specific methodology within that scheme they want to follow. This methodology can be either the so-called ‘basic modality’, which only entails the aggregation of the individual VAT results in a common return submitted by the group itself, or the so-called ‘advanced modality’, an imaginative formula that combines such aggregation with particular treatment of intra-group transactions, which are fully subject to VAT. This specific treatment of intra-group transactions has three distinctive features:

- A special rule to calculate the tax base, clearly distanced from the concept of ‘consideration’ obtained in return from the supply. More specifically, the taxable amount of intra-group transactions under the advanced modality will include the cost of every good and service directly or indirectly, totally or partially used to carry them out, as long as VAT has been paid for their acquisition.

- The consideration of intra-group transactions as a specific business sector. The goods and services used by the taxpayer to carry out intra-group transactions will be considered as the ‘inputs’ within this area of activity. The deductible proportion of VAT paid in respect of their acquisition must then be determined in accordance with the ‘special pro rata’ rule applicable in Spain, which reflects the taxpayer’s real use of such goods and services.

- The giving up of the exemptions provided for in Article 137 of the VAT Directive and all the exemptions included in Articles 132 and 135, i.e. concerning financial and insurance transactions, education, cultural services, hospital and medical care, etc.

From its origins, and due to the application of this particular set of rules, only the advanced modality has been regarded as a real VAT grouping scheme in a sense described in Article 11 of the VAT Directive. This is easy to understand if we pay attention to the intended aim of each modality: while the ‘basic modality’ just looks for administrative simplification, the ‘advanced modality’ aims to treat the group as a single taxpayer and to prevent VAT from harming businesses’ economic decisions. Combining this argument with the legal essence of EU directives (which bind MS as regards the result to be obtained but not also to the means to be used), we might conclude that the CJEU’s decision in Skandia America is fully applicable in Spain.

Personally, I do not share this interpretation and I do not think the answer can be so straightforward. I believe that we must be consistent: if we want to qualify the Spanish ‘invention’ as a real VAT grouping scheme, we need to evaluate whether such a regime fits into the content of Article 11 of the VAT Directive. This evaluation implies consideration not only of the literal meaning of such provision but also of the CJEU’s case law on this matter. Only when it has been demonstrated the actual validity of the Spanish formula based on EU law will we be in a position to address the implications of the Skandia America case in Spain.

Critical remarks

The fact that the Spanish VAT grouping regime represents a unique case in the EU context is beyond all doubt. However, such a circumstance should not necessarily lead to any conclusions concerning its (in)compatibility with EU Law.

Article 288 TFEU states that EU directives shall be binding, as to the result to be achieved, ‘but shall leave to the national authorities the choice of form and methods’. Focusing our attention on this point, we could argue that the Spanish VAT Act is fully compliant with EU law. It is based on a set of rules that lead to the same results as the non-chargeability of VAT to intra-group transactions, which is the rule followed by the other MSs. To reinforce this conclusion, we can recall two more arguments: first, that the Spanish Government consulted the VAT Committee before implementing the ‘imaginative formula’ described above, and second, that the EU Commission has never started an infringement procedure against Spain based on the functioning of the advanced modality’s VAT grouping provision.

However, the question is whether these circumstances would ensure the Spanish VAT grouping scheme’s survival if it were to be carefully scrutinised by the CJEU. In my opinion, the answer to this query is negative.

Whatever the historical background and the practical results the Spanish formula leads to, it is commonly known that every rule adopted by an MS in the field of VAT must be fully compliant with the principles of the VAT system, the objectives of the VAT Directive, and the interpretative guidelines concerning this regulation given by the CJEU. And the latter is precisely the point where the Spanish VAT scheme seems to fail.

After carrying out a thorough analysis of the Spanish formula, we realise that, whatever the VAT grouping’s modality, the Spanish VAT Act is distanced from the interpretative criteria supported by the CJEU in some important judgements. This is the case of Ampliscientifica and Amplifin (Case C-162/07), where the CJEU pointed out that the treatment as a single taxable person precludes the members of the group from continuing to be identified as individual taxable persons within and outside their group, and thus the Court justified the need to allocate a single VAT number to the group itself.

Far from adopting the CJEU’s guidelines on this issue, the Spanish VAT Act does not formally recognise the group as a single taxable person, nor does it treat it as such. Amongst other evidence, we consider that:

- there is no allocation of a single VAT number to the group;

- intra-group transactions are deemed as falling within the scope of VAT, although treated in a particular manner;

- group members keep their own status of individual taxpayers both within and outside the group. This means that the group’s members retain their own VAT number, act as independent economic operators with third parties, and are responsible for issuing the corresponding invoices and exercise the right to deduct on an individual basis.

In light of all these arguments (and others that we cannot recall here due to space constraints), the question is how long we will leave the Spanish VAT grouping scheme’s incompatibility with EU law unaddressed.

Back to the origin of the problem…

Whether we like it or not, the Spanish VAT grouping scheme does not treat the group as a single taxable person for VAT purposes. In light of the CJEU’s case law, no other interpretation is possible.

Perhaps, the time has come to reassess the Spanish ‘imaginative formula’ and look for a more orthodox one. Meanwhile, Spain has to deal with the drawbacks of being different. Among those drawbacks, there is certainly the fact of reaching no clear conclusions when evaluating the impact of the CJEU’s decisions for VAT grouping in Spain.

© 2021 Kluwer Law International B.V., all rights reserved.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer International Tax Blog, please subscribe here.