The Champions League is back in town and tonight, its iconic hymn echoes through the speakers of Europe’s greatest clubs’ mostly empty stadiums: “Die Meister! Die Besten! Les grandes équipes! The champions!”

To my personal delight, I’ve always found football more fun than I found it to be important. Like every year, my favourite and local FC (the illustrious ‘Alles Door Oefening Den Haag’ for those who may wonder) will not be a CL candidate for this edition. And like every year as well, the spectators and favorites are those fact-of-life and historic English, German, and especially Spanish top clubs. And how a club becomes such a top clubs, can be summarized with a cycle that renders the same whichever step is first: (1) more money, (2) better access to rare quality players, (3) more winnings, (4) more supporters, (5) more money, etc.

To support this notion: the bookies’ favorites list (for example the one published by Sports Betting Dime[1]) includes the likes of FC Barcelona, Bayern Munich, Real Madrid, and Liverpool, and largely matches Deloitte’s annual “Money League”[2] list of the world’s richest football clubs. One could wonder whether the surprise element in top football is fading away partly because of this, and whether perhaps a more ‘level playing field’, which could for instance be achieved with more stringent financial fair play rules, would be good for the sport as a whole.

And rest assured, I understand non-football-fans’ cynicism about the football fans seemingly irrational fascination with the annual repeat business that European top football has become, but football still evokes the tribal war-like emotions that apparently lurk in those of us. And so: we keep on watching well-compensated mercenaries do what many of us dreamed we would when we were little boys: playing at one of Die Besten, Les Grandes Équipes, The Champions.

FC Barcelona: top club with state aid?

One of those Champions, of course is FC Barcelona. And before it is ‘football’ again these weeks, my (sports) day as a tax lawyer begins with reading the newly published Conclusion by Giovanni Petruzella, Advocate General at the European Court of Justice. Its topic: The European Court must reassess FC Barcelona’s state Aid case.[3] Now this is a read I want to sit down for. As a ‘top teams status quo’- criticist (but also as a somewhat envious supporter of a low-performing team, or course), digging through a sharp case at the crossroads between life’s most important main issue (taxation) and its most important side issue (football) seems like all one could ask for.

What is the historic panorama? Four Spanish football clubs received approval in 1990 to continue operations as an ‘association’ instead of having to reorganize as a ‘sports company’.

Spain is a major sports country and (as such?) it has a legal form designated for clubs: the “S.A.D.”, acronym for the ´Soceidad Anonima Deportiva’[4]. In the nineties, when Spanish sports as a whole was in a problematic debt situation, the government obligated all professional sports clubs to reorganize themselves into such a corporate legal form, as it was reasoned that this would encourage good governance. After all, just like a ‘regular’ commercial organization, the directors bear some liability for (financial) mismanagement. However, an exemption was granted to sports clubs that had already demonstrated good governance in the years prior, being the four clubs that had been profitable in previous years. As A-G Petruzella puts it:

“ Under Ley 10/1990 del Deporte (Law 10/1990 on sports) of 15 October 1990 [5] (‘Law 10/1990′), all Spanish professional sports clubs were obliged to become sociedades anonimas deportivas (sports companies with limited liability; hereinafter: SADs’). The purpose of the provision was to encourage more responsible management of the clubs’ activities by adapting their legal form.

However, the seventh additional provision of Law 10/1990 provided for an exception for professional football clubs that had achieved a positive balance in the tax years prior to the adoption of this provision. This exception implied that these clubs had the opportunity to continue their activities in the form of sports clubs [associations, ed.]. The only professional football clubs to be covered by this exemption were FC Barcelona and three other clubs [Club Atlético Osasuna, Athletic Club and Real Madrid], all of which have made use of this option.

6. Unlike SADs, sports clubs are non-profit legal entities and are subjected to a special tax rate over their income. Until 2016 this rate was lower than the rate for SADs.

In other words: the four Spanish clubs that could continue to organize themselves as a ‘sports club’ or association, were deemed to be non-profit organizations. And until 2016, any profits they made nonetheless, were subject to a lower rate than those of the other clubs, organized as SADs. The difference between the two categories so created, therefore springs from two elements: (1) ‘sports’ are classified as a public benefit purpose, justifying that any profits a sports club generated but reinvested into sports within 4 years, were exempt from taxation[6], and (2) the remaining (non-reinvested) profits were taxed at a lower rate than the standard corporate income tax rate, to which sports companies (SADs) were subject until 2016[7] (note: the tax rate difference has since been eliminated). As the Commission summarized this coincidence of circumstances in their instruction to Spain to end the exception:

“the treatment of sports clubs differs from the tax regime that applies to sports companies with limited liability, which are subject to general corporate tax. Sports clubs as non-profit entities, […] qualify for a partial exemption from corporate tax […] under Spanish corporate law. [That Act] [also] provides that exempted clubs as non-profit entities, because of this partial exemption on their commercial income, pay the reduced corporate tax rate of 25% instead of the current general rate of 30% (35% until 2006 and 32, 5% in 2007).”

And why was it so important to end this regime? As the Commission noted in their decision to end that exemption, there was a significant correlation between the resources available to a football club and its sporting successes, meaning that this tax measure would harm competition. And this time around, it was the most visible form of competition in the Union: the pinnacle of the continent’s ‘National Sports’:

The activities from which the revenues arises are economic in nature and are carried out in a competitive competition with the other major European professional football clubs. The source of income is linked to the victories that the teams achieve in sporting competitions. The success of the teams, in turn, depends heavily on the resources available to the clubs to attract or retain the best players and coaches. Tax differentiation can [therefore] selectively favor the four clubs.

Now, of course, it would be difficult to measure whether there is really is a causal relationship between the Sports Club regime and the sporting success, but statistical support does seem to be found afterwards by looking at the incidence with which a Sports Club appeared in the list of Champion’s League Winners of the last 10 years and their opponents in the Knockout Stage:[8]

Does this mean that the regime difference forms inadmissible State Aid?

This same question arose before the European Court of Justice following the appeal brought by FC Barcelona against the decision taken by the Commission on this Spanish exemption-rule, in which it orders Spain to withdraw its exemption-rule[9]. And in order to walk along that path of tax theory, one must have a clear definition of such state aid. As the technical description derived from European case law is rather extensive, we quote the striking summary used by the European Commission itself on their info page (yes, the source is a bit unofficial, but the wording is effective):[10]

What is State Aid?

State aid is defined as an advantage in any form whatsoever conferred on a selective basis to undertakings by national public authorities. Therefore, subsidies granted to individuals or general measures open to all enterprises are not covered by this prohibition and do not constitute state aid (examples include general taxation measures or employment legislation).

Why control State Aid?

A company which receives government support gains an advantage over its competitors. Therefore, the Treaty[11] generally prohibits State aid unless it is justified by reasons of general economic development. To ensure that this prohibition is respected and exemptions are applied equally across the European Union, the European Commission is in charge of ensuring that State aid complies with EU rules.

In 2019, the European Court of Justice ruled in favor of FC Barcelona and its three sports club allies on this appeal. Reason being that the Commission was judged to have insufficiently proven that the three sports clubs indeed enjoyed a (structural) advantage compared to their rival SADs on the basis of this regime.

What caused doubt? The four sports clubs successfully argued that the tax regime for S.A.Ds also entailed specific beneficial arrangements that did not apply to sports clubs, such as an accelerated depreciation regime for purchased players, lowering the taxable base. And those benefits could lead to a significant reduction in their tax base, so the mere observation that sports clubs pay a lower statutory rate on their remaining profits would not be sufficient reason to conclude that the different regime resulted in a structurally lower tax burden over several year. Conclusion: there is insufficient grounds for concluding on a tax benefit. In fact, Real Madrid argued that their sport-club status itself was actually disadvantageous. From the press release of the General Court following their ruling:[12]

“[…] the examination of the resulting advantage cannot be dissociated from that of the other components of the tax regime of non-profit organisations. The Court points out […] that […] Real Madrid Club de Fútbol had observed that the tax deduction for the reinvestment of extraordinary profits was higher for [S.A.D.’s] than for non-profit entities [sports clubs]. The Madrid club claimed that that deduction was potentially very significant due to the practice of player transfers, as profits could be reinvested in the purchase of new players and that the tax regime applicable to non-profit organisations had thus been, between 2000 and 2013, ‘significantly more disadvantageous’ to it than that applicable to SPLCs.”

So long story short: there is indeed a difference, but the Commission, as the plaintiff, has the burden of proof to demonstrate that this difference leads to a structural advantage, and the General Court did not consider this latter point point proven.

The Commission obviously disagreed with this ‘judgement ricocheting on formalities’ and lodged an appeal with the European Court. The A-G now concludes (thus: advises) that the Court of Appeal refers the case back to the General Court, with an investigative instruction:

[I note] that the Commission [has already noted in the decision] that […] the tax credit associated with the tax deduction [for SADs] for the reinvestment of exceptional profits was not systematically granted, but only under certain conditions which were not always met, which means that this credit could not systematically neutralize the advantage obtained from the preferential tax rate in every tax year. Second, the Commission stated [in the decision] that the real impact of this deduction is considered when quantifying the aid by examining [ex post] for each tax year whether a benefit has arisen. The Commission’s approach […] thus appears to be in line with my [comparison requirements]. […] It follows that [the Commission’s appeal is justified, and that the judgment of the General Court should be set aside], and the case […] must be referred to the General Court for an examination of those arguments. and resources.

In other words: The General Court must find out whether the accounting proves that these sports clubs ultimately and structurally paid less than SADs, or not. If so, the regime may constitute state aid, which must then be quantified and repaid to the State. And this could be a significant financial blow, and therefore in football, a sporting one as well…

How about Football’s history with State Aid? The mud throwing started in 2012!

State aid is an infringement of competition and few playing fields are examined as carefully as those made up of grass. Therefore, it is more vivid for many to zoom in on the question whether or not it is fair that FC Barcelona is one of the few that can pay Messi’s meter due to an individual tax favor, than it is to zoom in on the question whether the price that Starbucks pays its company roasting house would also be paid to an unrelated roaster. However, it comes down to the same thing: has competition been falsified through tax systematics?

An so naturally, such a question has been asked more often in football. I take you back to 2008: football clubs were having a hard time as a result of the economic crisis erupted. Therefore, many football clubs were to restructure, be it with or without the help of (local) governments. And what resulted, was that national governments were soon accusing each other of “State Aid” to their local FCs.

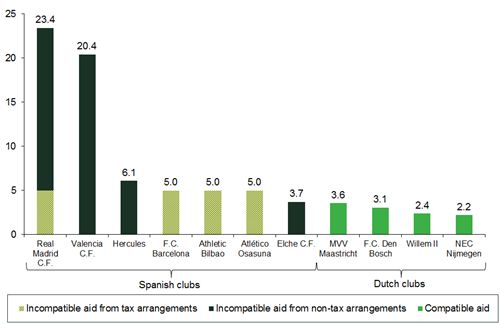

During that cycle, some Dutch football clubs were under attack. Clubs like FC Den Bosch and MVV Maastricht (charming, but by no means ‘Grandes Équipes) restructured with help from the municipality, who would, for instance, buy the land under the stadium from the football club (with a buy-back option) and then lease it back to them, generating a cash injection for the football club in exchange for a higher burn rate during the years after.

Encouraged by other Member States to this end, the European Commission set out to investigate these restructurings for state aid elements. After their investigation, the Commission ruled in 2015[13] that these transactions, the most notable one of which was the stadium sale-and-leaseback agreement between the municipality of Eindhoven and their local football club team PSV’s, in fact did not constitute state aid. This was concluded as the investigation showed that the pricing set in these sale-and-leaseback agreements, was at an arm’s length level.[14] In other words: the clubs did not receive a benefit, but entered into agreements with their local governments under business conditions.

In Spain, local governments were involved in football restructuring as well.

But the Spanish clubs came off less graciously, especially when the Spanish Minister of Sport suggested in 2013 to cancel their identified tax debts.

Because in this ‘football-state-support-storm’, a 2013 parliamentary inquiry led by Spain’s left-wing opposition showed that the Spanish professional clubs together had an outstanding tax liability of €750.000.000 of unpaid profit taxes, and an additional €660.000.000 of unpaid social premiums.[15] And this balance only included the sports companies (SADs); the Spanish government did not release the figures of the four sports clubs as their debts could potentially be traced back to them individually given their limited number. And adding fuel to the opposition’s fire, certain land transactions between local governments and football clubs simultaneously took place in Spain, and these were in fact classified as state aid due to the conditions deviating from market prices.[16]

When the Spanish State Secretary for Sports then suggested helping the clubs through the crisis by cancelling their long-term tax debts, European outrage ensued and the Commission opened a wide range of investigations.[17] The Spanish government backed down from their cancellation plan under this pressure and that of the left-wing opposition, and La Liga (Spain’s highest professional football league) was obliged to sign a covenant to have their teams reduce their tax debts to 35% of their 2013 position by the end of 2015, with La Liga’s television rights (otherwise distributed amongst the teams) serving as a collateral.[18]

This whole ordeal turned out to be a diplomatic dumpster fire[19] because the sitting European Commissioner for Competition was Joaquin Almunia.[20] A Spaniard who, to make matters worse, also occasionally hinted at his club preference for Athletic Club (one of the four sports clubs), and was subsequently accused by the FC Barcelona or Real Madrid loving part of the Spanish population (roughly 58% of Spanish football fans in total[21]) of impure motives in ‘tackling’ the top clubs. At the same time, however, he was accused by the European Ombudsman of delaying the investigations, because he would also hit ‘his own’ club with the ‘Sports club vs SAD’ part of the research! Now that is a lesson for politicians when referring back the ‘tribal warfare’ parallel we stated earlier in this piece: never state club preference. Never.

Now what will we see for the remainder of this Champions League season?

There is similarity between the 2012 financial landscape and this year’s Corona-Champions League season: we are amidst a recession and because of it, the relationships are more on edge between the higher GDPPC-states who are usually net contributors to the European Budget, and the lower-GDPPC-states who are usually receivers from said budget on the other.

Because just like in 2012, in many ‘Northern Europeans’, and especially those living in the ‘Frugal Four’ as actually identified by ‘Spain’ and its allies in such, perceive the Spanish state as being significantly bailed out by under the European Covid relief plan.[22] And incidentally, Spain believes that without Northern ‘tax havens’ they did not need a bail-out at all.[23]

And the context of football only makes this already emotional juxtaposition worse. As a self-perceived highly taxed Northern European, you may watch with sorrow how ‘your club’ gets humiliated on the pitch by a rich Spanish top club, which we now know may enjoy tax state aid from a state that declares itself on the edge of financial collapse and in need of solidarity. And so football shows itself again as the tribal war that makes it so much fun to watch. And sports seem to be a catalyst for political debate: can countries that provide prohibited State aid still appeal to European aide?

This debate is complicated, not in the last place the allegations of state aid are so widespread, and the investigations so many. Any state can counter accusations or moralistic talk from another Member State by pointing to their criticaster’s own not-so-holy track record. And the same goes for the European people as consumers and as voters: can one be critical of Apple’s Transfer Pricing methodology and still buy an FC Barcelona jersey? And can one despise Booking.com’s appeal to the Netherlands’ Covid wage subsidies yet still cheer if Real Madrid survive the group stage again?

I personally would not find that morally consistent, but then again, I work for a firm and I support a hot mess of a local FC. So it’s easy talking for me, as ‘we’ will likely never generate enough exposure to warrant an investigation by Margarethe Vestager. Nevertheless, such research into FC Barcelona makes me like them a little bit more, as it gives me a great opportunity to shed some light on my real hobby that I do in fact find important, nerding on taxation.

So whatever happens in this year’s edition of the Champions League, I will forever remember it and wonder: does state aid actually make competition less interesting, or more!

[1] https://www.sportsbettingdime.com/soccer/uefa-champions-cup-odds/

[2] https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/sports-business-group/articles/deloitte-football-money-league.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%253A+DeloitteGlobal+%2528Deloitte+Global+headlines%2529

[3] http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf text=&docid=232468&pageIndex=0&doclang=NL&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=9309015#Footnote1

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sociedad_An%C3%B3nima_Deportiva

[5] http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=232468&pageIndex=0&doclang=NL&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=9309015#Footnote3

[6] https://www.tba-associates.com/incorporating-a-foundation-in-spain-legal-and-fiscal-profile#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20corporate%20tax,income%20is%20taxed%20at%2025%25.

[7] https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2019-02/cp190017en.pdf

[8] https://media-exp1.licdn.com/dms/image/C4E12AQH6HaAUQETtZA/article-inline_image-shrink_1500_2232/0/1603807864127?e=1618444800&v=beta&t=7Cwks6gsuvVGaRcdmZqDoPU6CW17MLaGFPY4HWKGlF8

[9] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/NL/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32016D2391&from=EN

[10] https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/overview/index_en.html

[11] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:12008E107:EN:NOT

[12] https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2019-02/cp190017en.pdf

[13] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_16_2402

[14] https://www.ed.nl/default/brussel-gronddeal-tussen-gemeente-eindhoven-en-psv-was-geen-staatssteun-video~a6bfbc4d/?referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F

[15] https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-352250347/spanish-football-clubs-tax-debt-awakes-storm

[16] https://www.oxera.com/agenda/assessing-state-aid-in-the-beautiful-game/

[17] https://euobserver.com/news/122546

[18] https://footballperspectives.org/plan-relieve-spanish-football-club-tax-debts/

[19] https://euobserver.com/news/122546

[20] https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joaqu%C3%ADn_Almunia

[21] http://www.cis.es/cis/export/sites/default/-Archivos/Marginales/2700_2719/2705/Es2705mar_A.pdf

[22] https://www.dutchnews.nl/news/2020/07/coronavirus-eu-bailout-came-close-to-failure-says-rutte/

[23] https://www.taxjustice.net/2020/04/08/revealed-netherlands-blocking-eus-covid19-recovery-plan-has-cost-eu-countries-10bn-in-lost-corporate-tax-a-year/

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer International Tax Blog, please subscribe here.