The author would like to give thanks to Professor Daniel Gutmann, Professor Georg Kofler, and Simon Whitehead for an engaging and intellectually stimulating exchange of views on the CJEU’s judgment in X BV case through the emails. This post benefitted from it. However, the author is solely responsible for its content and no views expressed therein can be attributed to anyone except the author.

1. Introduction

1.1 Focus of this post

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) judgment of 4 October 2024 in X BV (C-585/22) is clearly one of the landmark cases determining the compatibility of domestic anti-tax avoidance rules with EU primary law. Although the CJEU concluded that the Dutch anti-tax avoidance rule in question – Art. 10a of the Dutch corporate income tax act (CITA) – is compatible with EU primary law (the freedom of establishment, Art. 49 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, TFEU), it does not herald the lost for the taxpayer. It is now the interpretative task for the Dutch Supreme Court (Hoge Raad der Nederlanden) to carefully assess the facts of the X BV case to identify whether the abuse existed in accordance with the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights (Cf. Kokott 2022, § 2.C). To this end, the Dutch Supreme Court must resist temptation to interpret Art. 10a CITA in line with its own antiabuse judicial doctrine fraus legis. Rather, it must follow the CJEU’s interpretative guidance in line with the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights. Only if the Dutch Supreme Court finds the abuse in accordance with such guidance, Art. 10a CITA could be applied by the Dutch tax authorities to deny the full interest on the loan paid by X to C in accordance with Art. 49 TFEU (section 4 below). This is the focus on the post. However, X BV is of vital importance to tax practitioners at least for the two other reasons, as briefly summarized in the two following paragraphs of this introduction.

1.2 X BV nuanced the interplay between the arm’s length principle and the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights in comparison to Lexel

The judgment in X BV nuanced the interplay between the arm’s length principle and the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights in comparison to Lexel (C-484/19) by confirming the overarching importance of valid commercial reasons (also called: economic reality or genuine economic activity) to identify abuse. Arm’s length terms of intra-group loans cannot secure against the qualification as “abusive practices’”, if the loans do not have valid commercial reasons apart from obtaining tax benefits, which contradict the purpose of relevant tax provisions and EU law. In other words, arm’s length conditions do not apply as a fully-fledged safe harbour for the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights (see paras 75-77 and 86-88 – whenever this post refers to para. or paras without any other indication, it is the reference to X BV). It will certainly complicate passing the muster of non-abusive transactions and arrangements involving intra-group loans and other payments subject to arm’s length examination, e.g. structures with central corporate treasuries.

1.3 The CJEU distinguishes between the Swedish anti-aggressive tax planning legislation in Lexel and the Dutch anti-tax avoidance legislation in X BV

The CJEU distinguishes between the Swedish anti-aggressive tax planning legislation in Lexel and the Dutch anti-tax avoidance legislation in X BV (para. 80). Although both captured arm’s length transactions, only the Dutch one operated by allowing taxpayers involved in intra-group financing to rebut the presumption of abuse by valid commercial reasons. By the same token, only the Dutch legislation gave decisive value to the valid commercial reasons while the Swedish legislation did so towards the intention to obtain a tax benefit. The Swedish legislation, therefore, was not compatible with the two-fold test of abuse, as established by the CJEU case law and applied consistently within the scope of the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights. Likewise, a powerful movement against “aggressive tax planning” and tax competition orchestrated by the European Commission in concert with the OECD (e.g. the European Commission 2012; Securing the activity framework of enablers (SAFE); Unshell Proposal; the OECD’s BEPS Action Plan 2013, p. 13; the OECD Pillar Two; in literature see Dourado 2015; Kuźniacki 2022; Kuźniacki 2023;Kuźniacki & Visser 2024) does not constitute a justification to restrict fundamental freedoms by means of prevention of tax avoidance in line with the CJEU case law and the general principles of EU law, i.e. the principle of proportionality, the principle of legal certainty and the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights (cf. paras 80-85, 89-92; Lexel, paras 52-57).

1.4 Outline of the post

Before the main analysis unfolds, sections 2 and 3 below present key facts of the X BV case and a very brief summary of the CJEU’s decision, respectively. The main analysis in section 4 below aims to provide the answer to the question why the Dutch Supreme Court must resist the temptation of “fraus legis” to follow the CJEU’s interpretative guidance in X BV. Moreover, the readers shall be aware that comprehensive publications on the theme of this post are under construction by the present author to cover the impact of that judgment in the key areas mentioned in sections 1.2-1.3 above.

2. Facts, dispute and preliminary questions

A dispute arose between X BV (a Dutch tax resident company), and the Staatssecretaris van Financiën (Dutch Secretary of State for Finance, hereinafter “Dutch tax authorities”) regarding the right to deduct (for the Dutch income tax purposes) the interest paid on an intra-group loan in order to finance the acquisition of a company not related to the existing group of companies.

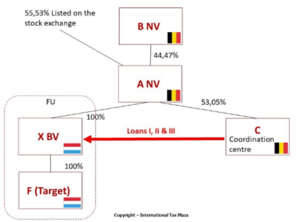

The dispute arose in the following factual circumstances: X belonged to a multinational group of companies, including companies A and C (Belgium tax residents). A was the sole shareholder of X and the majority shareholder of C. In 2000, X acquired the majority of the shares in F, a Dutch tax resident company. A acquired the remaining shares in F. X financed that acquisition by means of loans contracted with C, which used for that purpose own funds obtained through a capital contribution made by A. As a result of that acquisition, X and F belonged to the same group and constituted the so called fiscal-unity under the Dutch tax law. Thus, their taxation took place on the basis of full consolidation of assets and liabilities and profits and losses as if they were a single taxpayer (paras 4-7).

Interestingly, the Dutch Supreme Court did not provide the CJEU with the following, publicly available facts, as stemming from the proceedings before the Dutch Appeal court in X BV (Gerechtshof Arnhem-Leeuwarden of 2 October 2020, ECLI:NL:GHARL:2020:8628). They reveal that C had 36 full time employees in 2000 and this number increased to 375 as of 2008 (para. 2.6). C provided loans on a regular basis to all entities of the group, including X, which, in turn, transferred their excess cash to C.

Final structure based on facts of X BV case

In 2007, the Dutch tax authorities refused to allow X to deduct interest paid to C in line with Art. 10a CITA. It said that the deduction of interest on loans contracted with related parties, in particular for internal reorganizations or external acquisitions, was restricted if, among the others, subject to certain conditions, the loan was, in law or in fact, directly or indirectly, linked to the acquisition or increase of a participation by the taxpayer, by an entity that is related to the taxpayer and subject to corporate income tax (CIT), or by an individual who is related to the taxpayer and resides in the Netherlands, in an entity that, as a result of this acquisition or increase of participation, becomes an entity related to the taxpayer.

The transaction of the acquisition of F by X fell within the mentioned scope of application of Art. 10a CITA. However, the taxpayer (e.g. X) could retain the right to the deduction of interest if it made plausible that 1) the loan and the related transactions were based, to a decisive extent, on economic considerations, or 2) the “compensatory tax test” has been passed, i.e. the creditor was subject to CIT on the loan interest at least 10% on profits calculated in accordance with CITA.

X challenged denial of deduction by the Dutch tax authorities before the Gelderland District Court and, subsequently, before the Dutch Court of Appeal. The latter court ruled on 20 October 2020 that Articles 49, 56, and 63 TFEU did not preclude the limitation of the interest deduction provided for in Article 10a CITA. X appealed to the Dutch Supreme Court, which referred three preliminary questions to the CJEU, seeking clarification of its previous judgment in Lexel in which the CJEU ruled that transactions at arm’s length are not abusive.

By asking the three questions, considered together, the Dutch Supreme Court seek to know whether: the Articles 49, 56, and 63 TFEU must be interpreted as precluding national legislation under which, in determining a taxpayer’s income, the deduction of interest paid on a loan contracted with a related entity, related to the acquisition or increase of a participation in another entity, which becomes, following this acquisition or increase, a related entity to this taxpayer, is entirely refused when this debt is considered to constitute a purely artificial arrangement or to be part of such an arrangement, even if the said debt was contracted under arm’s length conditions (arm’s length loan) and if the amount of this interest does not exceed what would have been agreed between independent enterprises (arm’s length interest rate).

3. The CJEU’s decision in a nutshell

This section is only an extremely short summary of the CJEU decision in X BV to keep this post as concise as possible. I kindly refer all readers to consult the content of the decision while reading sections 4 of this blog post.

In the judgment on X BV, the CJEU followed Advocate General (AG) Emiliou opinion on X BV , to consider Art. 10a CITA compatible with Art. 49 TFEU. However, it did not entirely follow the reasoning and the proposition of the AG to reverse the observations in Lexel (para. 56) regarding the treatment of arm’s length principle vis-à-vis one of the general principles of EU law – prohibition of abuse of rights. Rather, the Court nuanced and adjusted its observations in Lexel to the case at hand, considering legal and factual differences between those cases (paras 74-88).

Considering all of the abovementioned reasoning, the CJEU concluded that Art. 49 TFEU “must be interpreted as not precluding national legislation under which, in the determination of a taxpayer’s profits, the deduction of interest paid in respect of a loan debt contracted with a related entity, relating to the acquisition or extension of an interest in another entity which becomes, as a result of that acquisition or extension, an entity related to that taxpayer is to be refused in full, where that debt is considered to constitute a wholly artificial arrangement or is part of such an arrangement, even if that debt was incurred on an arm’s length basis and the amount of that interest does not exceed that which would have been agreed between independent undertakings.”

4. Will the Dutch Supreme Court resist the temptation of “fraus legis” and follow the CJEU’s interpretative guidance in X BV? If not, it may fail to respect EU primary law

4.1 Facts of the X BV case do not seem to indicate abuse in line with the CJEU’s interpretative guidance in that case and the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights

The CJEU judgment in X BV provided the Dutch Supreme Court with the interpretative guidance on how to apply Art. 10a CITA in line with Lexel and other case law shaping contours of the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights. The economic reality (i.e. valid commercial reasons), objectively verifiable by third parties, constituted almost the entire centre of gravity of such an interpretation, while the subjective tax avoidance intention barely oscillated around the edges of the CJEU’s attention. Indeed, the concepts of economic reality and abuse are closely interlinked with each other so that the lack of the former implies the existence of the latter (Cf. Kokott 2022, p. 75).

The Dutch Supreme Court’s interpretative task requires the application of the interpretative guidance from X BV to the facts, to decide whether or not they indicate abusive practice in accordance with the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights. One of the key parts of that guidance regards the need for a more holistic approach to identify abusive tax avoidance rather than focusing only on the arm’s length terms of the loan provided by C to X, or other formal elements concerning that loan (para. 78).

In the author’s opinion, such a holistic approach to assess abuse in light of the facts of X BV do not indicate abuse. The main reason for that is the fact that A regularly made equity contributions to C, which was the corporate central treasury of the group employing high-skilled finance managers (nearly 400 own employees by 2008). C provided loans on a regular basis to all entities of the group, including X, which, in turn, transferred their excess cash to C. There was, therefore, the economic reality (the valid commercial reasons) in providing the loans in the entire group by C and sufficient degree of relevant economic substance to genuinely do so without any circularity among the transactions that would cancel out each other’s effect, i.e. factual circumstances supporting the existence of valid commercial reasons and the capability of their genuine enforcement (cf. Navarro 2024, pp.19-22).

4.2 Why must the Dutch Supreme Court resist the temptation of “fraus legis” to follow the CJEU’s interpretative guidance in X BV?

The question is now whether the Dutch Supreme Court will meticulously follow the interpretative guidance of the CJEU to identify abuse or its lack in X BV, or it will apply own judicial antiabuse doctrine “fraus legis” to this end. The temptation to do the latter may be high insofar as Art. 10a CITA constitutes the codified judicial antiabuse doctrine “fraus legis”, as arising from the anti-profit drainage case law of the Dutch Supreme Court, bespoke to intra-group loans for purposes of internal or external acquisitions (De Wilde & Wisman 2016, section III.7.2).

Both Art. 267 TFEU and the principle of autonomy of EU terms and concepts (CILFIT (283/81), paras 19-20; For the autonomy of concepts relevant to tax law see Monsenego 2011, p. 23) require the Dutch Supreme Court to detach from its own vision of abuse, as stemming from fraus legis, and to identify of abuse in X BV considering the facts of that case in accordance with the interpretative guidance of the CJEU, which, in turn, stems from the principle of prohibition abuse of rights. The mentioned principle of autonomy also aims to ensure the fullest possible achievement of EU purposes in conformity with the principles guiding the functioning of the EU (Kuźniacki 2022, p. 71). Moreover, such principle is the source of the principle of effectiveness of EU law and the interpretative directive effet utile (Advocate General E. Sharpston opinion on Stichting Centraal Begeleidingsorgaan voor de Intercollegiale Toetsing (C-407/07), para. 13). Departing from the CJEU interpretive guidance in X BV in favor of fraus legis by the Dutch Supreme Court would jeopardise a compatibility of its judgment with all of the above mentioned principles of EU law.

4.3 Will the Dutch Supreme Court resist the temptation of “fraus legis” to follow the CJEU’s interpretative guidance in X BV?

In light of the foregoing, the Dutch Supreme Court must also factor in that its fraus legis doctrine was developed to prevent abuse of domestic Dutch tax law whereas the CJEU developed the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights to prevent abuse of EU law by tax avoidance transactions or arrangements. X BV case is no longer only about prevention of abuse of the Dutch tax law, which would trigger the role of fraus legis and Art. 10a CITA, but about prevention of abuse of Art. 49 TFUE. The fraus legis doctrine and Art. 10a CITA are not bespoke to prevent abuse of Art. 49 TFEU. Even if the CJEU considered Art. 10a suitable to prevent tax avoidance stemming from “the artificial nature of the transactions concerned, arising from the redirection of own funds and the conversion of them in loan capital” (paras 61-64), the decisive part of the proportionality test (stricto sensu) is included later on in the CJEU judgment (paras 66-93), and contains the pivotal interpretative guidance to the Dutch Supreme Court. In that regard, it must be observed that Art. 10a CITA was clearly not targeting only abusive tax avoidance, as identified by the CJEU, to the extent to which it allowed taxpayers to escape the denial of deduction if the interest was subject to at least 10% of taxation (para. 3 with reference to Art. 10a(3)(b) CITA). A low taxation or no taxation is solely of no indication of abuse. It is at most, an indication of aggressive tax planning, which, in the CJEU’s view, is not a phenomenon the prevention of which constitutes an overriding reason in the public interest, justifying a restriction of Art. 49 TFEU (para. 59 with a reference to the Danish cases on interest (C-115/16, C-118/16, C-119/16 and C-299/16), para. 109 and the case-law cited). The CJEU explicitly considered a legislation preventing aggressive tax planning as incompatible with Art. 49 TFEU (para. 80 with a reference to Lexel, paras 52 to 54).

This shows that Art. 10a CITA, as emerged from fraus legis case law of the Dutch Supreme Court, is by no means a perfect match with the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights to prevent abuse of Art. 49 TFEU. If this Court follows its own judicial antiabuse doctrine to apply Art. 10a CITA to facts of X BV case instead of the CJEU’s interpretative guidance in line with the principle of prohibition of abuse of rights, it risks rendering a judgement violating the EU primary law. Presumably, the avoidance of that risk is sufficient for the judges of the Dutch Supreme Court to carefully follow the CJEU’s interpretative guidance. Certainly, the Dutch Supreme Court knows how to distinguish between aggressive tax planning and abusive tax avoidance. While the widespread legislative prevention of the former still is at the forefront of tax policy agendas of the European Commission and the OECD, only the latter constitutes an overriding reason in the public interest justifying a restriction of Art. 49 TFEU (para. 59 with a reference to the Danish cases on interest, para. 109 and the case-law cited).

Just as the CJEU must rigorously apply the general principles of EU law to prevent abusive tax avoidance to ensure a right balance between fiscal interests of EU Member States and individual freedoms of taxpayers at the EU level (cf. Schön 2020, sections 1, 6.3.1 & 7), the Dutch Supreme Court must do so in the Netherlands. Otherwise the liberating forces of the EU’s internal market will be restrained to the detriment of not only taxpayers but also the investment’s attractiveness of EU Member States on a global arena. This is in a square opposition to the current agenda of the Council of the EU to improve the EU competitiveness (Council of the EU 2024, p. 4). This is also, if not even more so, contrary to the Dutch global position as the world’s leading investment centre (IMF 2024).

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer International Tax Blog, please subscribe here.