(Forthcoming: Intertax, vol. 49, 2021, issue 6/7)

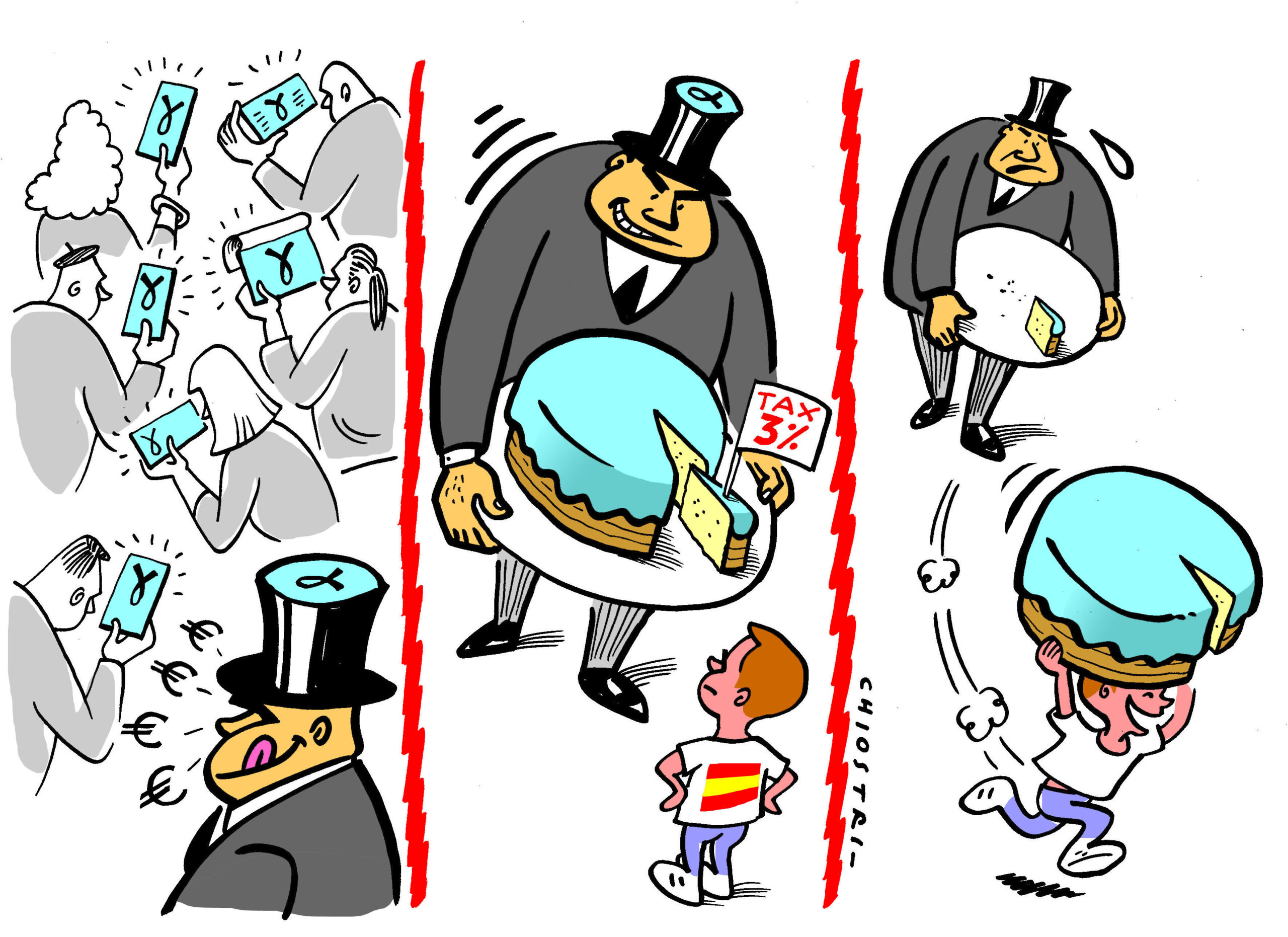

The Spanish digital services tax (hereinafter DST)[1] came into force 16 January 2021 replicating the European draft directive except for some minor deviations. In essence, it applies a 3% tax on the revenues obtained by taxpayers as a result of the supply of certain digital services to users located within the Spanish territory provided certain quantitative thresholds are surpassed. Covered digital services include:

- placing advertising on a digital interface that is targeted at users of the interface;

- making certain types of multi-sided digital interfaces to users, particularly those allowing them to find and interact with other users and those facilitating the provision of goods/services directly between them; and

- transmitting user data generated from their activities within digital interfaces.

The Spanish DST, just as with other DSTs that have become a reality in Europe, poses a number of advantages.

First of all, it has the undeniable merit of being the sole relevant proposal on the matter that has achieved the milestone of jumping from policy reports to national gazettes to date. Meanwhile, other proposals proposed by the EU, OECD, and UN are kept awaiting with resignation in the waiting room.

Second, it certainly contributes to the update of the tax systems by seizing some emblematic new business models belonging to the digital economy (e.g. social media, sharing economy platforms, online advertising, or transmission of user data) for which profits have largely been untaxed in the user jurisdictions to date.

Third, it will expectedly give rise to much-needed tax revenues in a moment when states are experiencing very difficult times as a result of the global pandemic.

Nevertheless, the current configuration of the bill entails a number of important risks and challenges at both a legal and administration perspective that should be carefully assessed.

First and foremost, the DST is likely to generate an unbearable level of legal uncertainty to targeted taxpayers. Taxpayers will be doomed to struggle with ambiguous clauses guiding the delimitation of the covered services and the calculation of the tax and will subsequently be required to calculate the taxable revenues on the basis of hardly traceable (and probably inaccessible) data. The Spanish tax administration will not be in a better position as it will most probably lack the necessary means to successfully challenge the tax assessment submitted by the taxpayer.

Second, difficulties arising from the application of ordinary methods of calculation will almost certainly condemn the parties to settle with the subsidiary method which is, in turn, based on obscure indicators with which the corresponding parties may play at their discretion to justify any outcome. Legal certainty is, once again, compromised.

Third, there is no way to prevent taxpayers from transferring the cost of the tax to either their consumers or business partners considering the monopolistic nature of potentially covered taxpayers. Indeed, such a risk already materialized in the case of both Amazon and Google Spain that recently announced a 3% and 2% increase, respectively, in the commission payable by their partners.

Ultimately, a careful assessment of the benefits, costs, and risks of the Spanish DST (an analysis that may be easily extrapolated to its European neighbors) casts doubts on the adequacy of the current configuration of the tax and, more generally, on its own existence.

© 2021 Kluwer Law International B.V., all rights reserved.

You can read the full version of this article in Intertax, vol. 49, 2021, issue 6/7.

[1] https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2020/10/16/pdfs/BOE-A-2020-12355.pdf

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer International Tax Blog, please subscribe here.