BEPS Action Plan 6 observes that corporations are misusing Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA) provisions by indulging in treaty shopping. A typical example of treaty abuse that BEPS Action Plan 6 seeks to counter is that of an American corporation entering the Indian market through Mauritius because of the favourable India-Mauritius DTAA. An intermediary mailbox company is opened in Mauritius to act as a conduit for investment into India. The India-Mauritius treaty was signed to avoid double taxation of income that arises in transactions between India and Mauritius. When this treaty is used by a company from a third country, it leads to treaty abuse.

To plug this loophole, BEPS Action 6 suggests the introduction of one of three provisions in all DTAAs:

- A Principal Purposes Test (PPT) rule

- A wider Limitation of Benefits (LOB) rule

- A PPT rule together with a simplified Limitation of Benefits (LOB) rule

The substance of the above action plan is to allow treaty benefits to a company from (say) Mauritius only if the company in Mauritius has genuine business in Mauritius. The principal purpose of the Mauritian-company is not to take benefit of the tax treaty, but to run a business in Mauritius. BEPS Action Plan 6 intends to make this amendment in all bilateral tax treaties through the Multilateral Instrument (MLI).

The eventual introduction of PPT and LOB clauses is expected to root out treaty abuse. It is speculated that PPT is a general anti-avoidance rule and will discourage a concern resident in a third country from taking advantage of a bilateral treaty. However, there are already concerns that some corporate structures are suited to indulge in treaty shopping in spite of PPT and LOB conditions. One such is the Protected Cell Company.

The Protected Cell Company

Protected Cell Companies (PCCs) are pre-structured in such a way that they manage to circumvent even the LOB and PPT clauses. Of course, the PPT clause is wide in scope and places substance over form. However, the very structure of a PCC is such that it may hoodwink an auditor or an investigator in believing that an investment rooted through a haven-based PCC for the principal purpose of investing in a source country conducts genuine business.

First introduced in Guernsey in 1977, PCCs consist of a “core” and several companies that are called “cells” within a single legal entity. Each cell is an independent unit and its assets and liabilities are ring-fenced from other cells.

I have concluded in my book Loophole Games that PCCs have become exceedingly popular as the structure itself obscures ownership interests and so can shelter proceeds of crime and fraud away from the prying eyes of law enforcement agencies. A cell may independently open bank accounts and run a business. But it is not a legal entity, so it is not bound to reveal information to authorities.

This can be illustrated with a hypothetical example. Say the government of China sends a reference to the government of Mauritius (assuming they have an exchange of information treaty) requesting for ownership details of a cell. The government of Mauritius will first send a regret that such an entity does not exist in its list of registered entities. Then the tax authorities of China will send another reference with specifics, which will help the Mauritius tax authorities identify the PCC. Then the Mauritius tax authorities will extract data on the PCC. All they will get is details of the “core” and names of the “cells”. By this time, the PCC and its constituent cells would become aware of roving enquiries. The cells will have sufficient time to move assets out of the PCC by the time the tax authorities ask for cell-level data.

How PCCs facilitate treaty shopping in LOB era

The key criteria of an LOB clause is to limit the benefit of a tax treaty only to concerns that have minimum activities and business operations in a treaty country (such as a minimum number of employees, local source for active income, etc). The key test for clearing the PPT clause is to demonstrate that the principal purpose of a company in a treaty state is to do business in that state.

Treaty shopping usually happens when a company resident in a third country uses a conduit in a treaty country to enter the other treaty country. All a tax lawyer has to do, to run a conduit, is open a PCC in a low tax jurisdiction (having a favourable tax treaty with the destination country) and make a local businessman run his business from one of the cells. Other cells will be given to clients who want to avail of treaty benefits. Since the PCC is a legal entity and individual cells are not, the cells and owners of cells will manage to get treaty benefits if the PCC as a whole fulfills the principal purpose test and substance test.

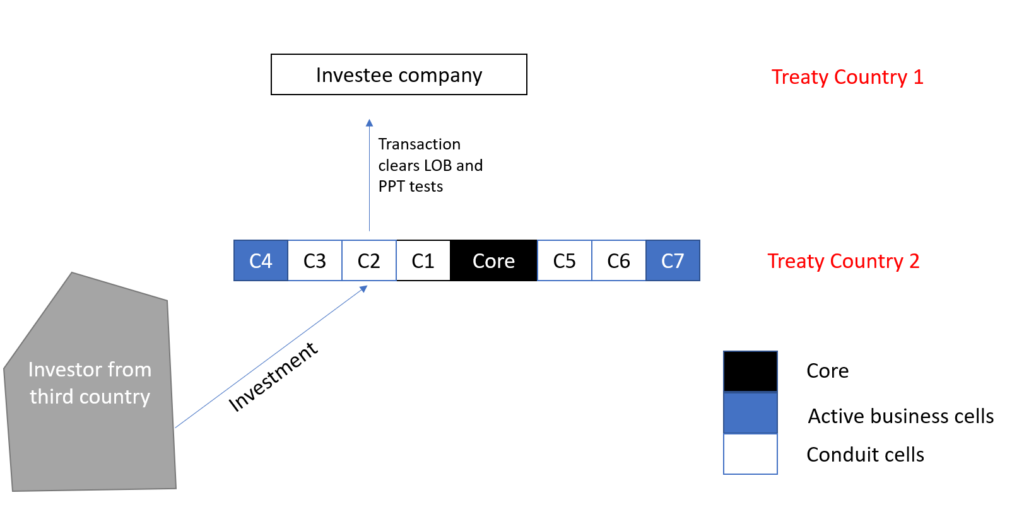

A graphic illustration of how a PCC structure can be misused to circumvent PPT and/or LOB clauses, showing how investment into a target company can be routed through a conduit in a country with treaty benefits is as under:

In the above illustration, Core is controlled by a tax lawyer in Treaty Country 2 that has favourable treaty terms with Treaty Country 1. Cells C4 and C7 run genuine business and employ genuine employees in Treaty Country 2. These cells are enough to qualify the PPT test. The entire PCC is a single company, and none of the cells has any separate legal existence. However, the law of PCC in tax havens is such that each cell is separately controlled by its holding firm. All cells have independent bank accounts and independent managers.

Possible solution to the problem of PCCs

A possible solution to the problem is for domestic tax departments to modify the transfer pricing declaration form and specifically ask a firm to declare the legal nature of its Associated Enterprises. Another possible solution is possible in countries that require cross-border transactions to be declared to the Central Bank. The Central Bank can specifically ask for the nature of legal entity transacted with by a resident firm. If the firm declares that its transaction is with a cell of a PCC, then red flags could be raised, or the case could be selected for deeper investigation.

However, if a firm in Treaty Country 1 does not give a true declaration of its Associated Enterprise in Treaty Country 2, it will be difficult for local auditors or investigators to detect the use of a PCC. Country-by-Country reporting (CbCR) does include risk parameters that will profile the conduit nation as a “suspicious jurisdiction” on the basis of a low effective tax rate. However, Table 2 of CbCR requires MNCs to declare the nature of business of a Constituent Entity (CE). The CE in this case will be the entire PCC rather than just the cell. The MNC may declare the active business of other cells of the PCC as the business of the PCC as a whole in Table 2 of CbCR. This adds a deceiving colour to the CbC report and lowers the risk quotient of the AE Cell.

But if detected by CbCR risk assessment parameters, the case will be flagged and assigned to an investigator. The investigator may then use the Exchange of Information treaty to arrive at the truth.

Views are personal.

The author is an officer of the Indian Revenue Service. His latest book, “Loophole Games: A Treatise on Tax Avoidance Strategies” has been published by Wolters Kluwers India and has been an Amazon bestseller.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer International Tax Blog, please subscribe here.