In a 207 page opinion the Tax Court ruled March 23, 2017 that the IRS’s adjustment with respect to Amazon.Inc’s transfer pricing buy-in payment for an intragroup cost sharing agreement (CSA) is arbitrary, capricious, and unreasonable [1]. Another major blow for the IRS in a string of such losses starting with VERITAS [2] (2009), the 2010 Xilinx [3] about-face of the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, the 2015 en banc Tax Court decision of Altera [4] and Medtronic in 2016 [5]. In that today’s 200 page opinion will require some digestion for a full analysis, this article provides historical context and some initial descriptive analysis of the Court’s decision relative to the positions argued by Amazon Inc. and the IRS.

The Tax Court held that Amazon’s choice of the comparable uncontrolled transaction (CUT) method with appropriate upward adjustments in several respects is the best method to determine the requisite buy-in payment. Moreover, the Court found that the IRS abused its discretion in determining that 100 percent of Technology and Content costs constitute Intangible Development Costs (IDCs), and that Amazon’s cost-allocation method with adjustments supplies a reasonable basis for allocating costs to IDCs.

The Court found that the IRS committed a series of errors in calculating the buy-in value of the preexisting intangibles. Amazon’s valuation was based upon a limited useful life of seven years or less for the preexisting intangibles whereas the IRS’ commissioned Horst Frisch Transfer Pricing Report assumed that the intangibles have a perpetual useful life. Under Amazon’s approach, after decaying or “ramping down” in value over a seven year period, Amazon’s website technology as it existed in January 2005 would have had relatively little value left by year-end 2011. But approximately 58 percent of the Horst Frisch Report proposed buy-in payment, or roughly $2 billion, is attributable to cash flows beginning in 2012 and continuing in perpetuity.

The Court found that the IRS committed a series of errors in calculating the buy-in value of the preexisting intangibles. Amazon’s valuation was based upon a limited useful life of seven years or less for the preexisting intangibles whereas the IRS’ commissioned Horst Frisch Transfer Pricing Report assumed that the intangibles have a perpetual useful life. Under Amazon’s approach, after decaying or “ramping down” in value over a seven year period, Amazon’s website technology as it existed in January 2005 would have had relatively little value left by year-end 2011. But approximately 58 percent of the Horst Frisch Report proposed buy-in payment, or roughly $2 billion, is attributable to cash flows beginning in 2012 and continuing in perpetuity.

Amazon cited the court’s decision in VERITAS [6] as one of the basis that the IRS’ adjustment with respect to the buy-in payment was arbitrary, capricious, and unreasonable. Like with VERITAS, in Amazon.com Inc the Tax Court again rejected the IRS’ approach of “aggregation” of the intangibles to determine valuation, holding it neither yields a reasonable means nor the most reliable one [7]. Specifically, the Court rejected the business-enterprise approach of aggregating pre-existing intangibles which are subject to the buy-in payment and subsequently developed intangibles which are not. Secondly the Court noted that the business-enterprise approach improperly aggregates compensable “intangibles” such as software programs and trademarks with residual business assets such as workforce in place and growth options that do not constitute “pre-existing intangible property” under the cost sharing regulations in effect during 2005-2006. Finally in this regard, the Court stated that the IRS ignored its own regulations whereby even if the IRS determines that a realistic alternative exists, the Commissioner “will not restructure the transaction as if the alternative had been adopted by the taxpayer,” so long as the taxpayer’s actual structure has economic substance [8].

String of Losses

Amazon.com Inc. (2017), VERITAS, Xilinx, Altera and Medtronic involved restructurings that transferred ownership of intellectual property and technology intangibles from a United States parent to its foreign subsidiary.

VERITAS granted its Ireland subsidiary the right to use certain preexisting intangibles in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia pursuant to its intragroup CSA. As consideration for the transfer of preexisting intangibles, its Ireland subsidiary made a $166 million buy-in payment to VERITAS based upon a CUT to calculate the payment. The IRS in a notice of deficiency chose a discounted cash flow income method with a resulting buy-in payment adjustment of $2.5 billion. Moreover, the IRS argued that the buy-in payment must take into account access to VERITAS’ research and development team, marketing team, distribution channels, customer lists, trademarks, trade names, brand names, and sales agreements. The Tax Court found the IRS’s determinations arbitrary, capricious, and unreasonable, and that instead VERITAS’ CUT method with appropriate adjustments is the best method to determine the requisite buy-in payment. The Tax Court found that the IRS’ discounted cash flow method was improperly used when the IRS valued the buy-in payment as if the intangibles had a perpetual useful life. The IRS issued an ‘action on decision’ that it disagreed with the Court’s factual determination and reasoning and thus would disregard the decision [9].

In Xilinx, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals withdrew its published earlier decision favoring a method promulgated by the IRS via its pre-2003 cost sharing agreement regulations (“CSA pre-2003”)and instead relied upon the arm’s length standard to determine the intragroup cost allocation. The Ninth Circuit held that that employee stock option (“ESO”) expenses in cost-sharing agreements related to developing intangible property are not subject to reallocation under the applicable CSA pre-2003 regulations. The Court concluded that third parties jointly developing intangibles and transacting on an arm’s length basis would not include ESO expenses in a cost sharing agreement. The IRS issued an action on decision whereby the IRS acquiesced in the Xilinx outcome but with two caveats [10]. The acquiescence only applied for taxable years prior to August 26, 2003 and the IRS did not acquiesce is the Court’s reasoning.

In Altera, currently on appeal to the U.S. Ninth Circuit, the Tax Court held that Treasury failed to support its belief with any evidence in the administrative record that third parties would share ESO costs, failed to articulate why all CSAs should be treated identically, and failed to respond to significant comments from industry received during the regulatory drafting process. Thus the Court held that Treasury’s final CSA regulations invalid because these failed to satisfy the U.S. Administrative Procedural Act required ‘reasoned decision making’ standard [11].

History of Cost Sharing Arrangement Regulations

Multinational groups share intellectual property (“IP”) within the group through license agreements or a cost sharing arrangement. A cost sharing arrangement involves related parties (the “controlled participants”) sharing among themselves the costs and risks associated with efforts to develop intangible property in return for each having an interest in any intangible property that may be produced (referred to in the 1995 QCSA Regulations, amended in 2003, as covered intangibles and in the 2009 Temporary Regulations and 2011 Final Regulations as cost shared intangibles. The QCSA Regulations were issued in 1995 and liberalized in 1996.. The QCSA regulations were tightened with respect to stock-based compensation in 2003, proposed regulations to replace the QCSA Regulations were issued in 2005, and a CSA-Audit Checklist was issued for existing CSAs which effectively required increased buy-in payments for pre-existing intangibles.[12] The tightening process continued with the CSA-CIP issued in September 2007 (withdrawn), the Temporary Regulations effective January 5, 2009 and the Final Regulations effective December 16, 2011.

The CSA-CIP provided that certain transfer pricing methods (the Income Method and the Acquisition Price Method) which are similar to the specified transfer pricing methods, set forth in the Temporary Regulations and the Final Regulations would typically be the best methods under the QCSA Regulations, even though they constituted unspecified methods under the QCSA Regulations.

Amazon’s Controversy and Outcome

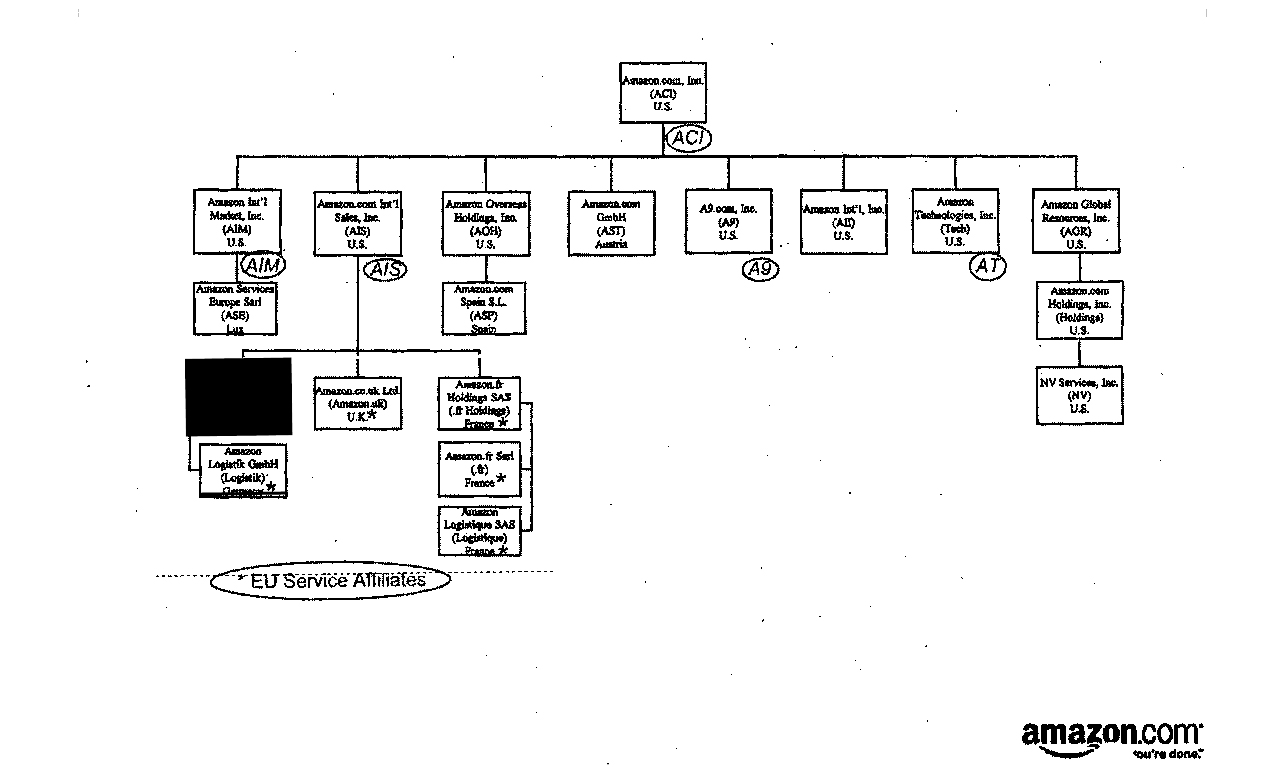

Amazon, as of its 2016 annual financial report, is a $44 billion company that relies on computer software and the internet to sell goods and services online. Amazon launched three Amazon-branded retail websites focused on European customers: Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.de in October of 1998, and Amazon.fr in August of 2000 (collectively, the “European Websites”). In an attempt to manage those sites from its headquarters in Seattle, Amazon entered into various intercompany service arrangements [13].

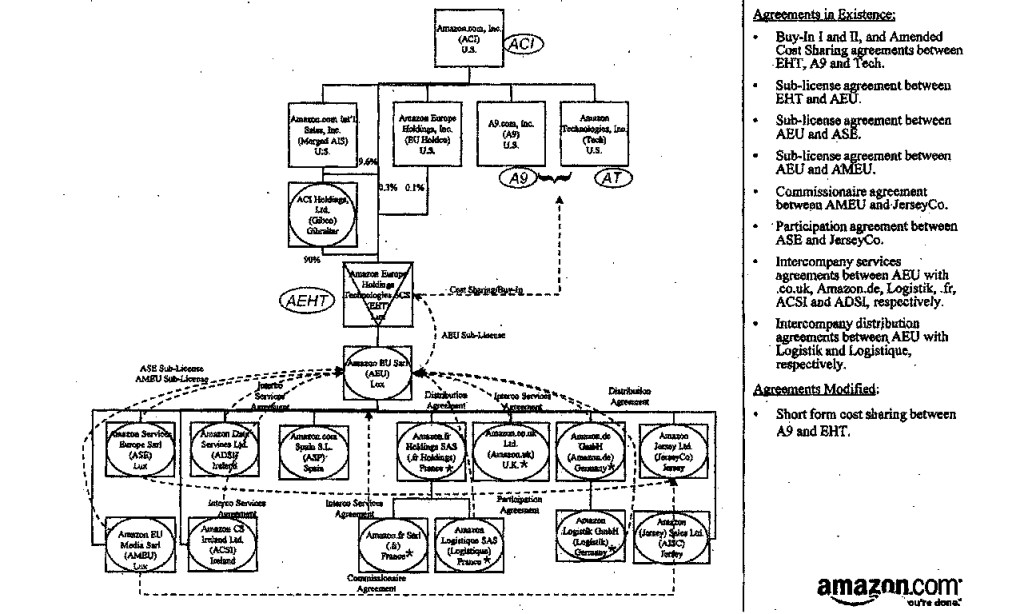

However, Amazon contended that it could not “simply re-launch the Amazon.com website in foreign countries” but rather, it had to launch sites that were “specifically tailored to the browsing practices, purchasing habits, [and] language and cultural preferences” of its European market. It also needed to develop new technology to support those European sales. Therefore, between June 2004 and April 2006, Amazon reorganized its European operations and moved the ownership and management of the websites to Luxembourg.

Effective Jan. 1, 2005 Amazon Inc., Luxembourg-based Amazon Europe Holding Technologies SCS (AEHT), and other related Amazon parties entered into a cost sharing arrangement under which they agreed to pool resources to develop new intangible property and to enhance the value of existing intangibles [14]. AEHT and Amazon agreed to share all costs associated with the development program in proportion to their respective reasonably anticipated benefits. These costs included research, development, marketing, and other activities. According to Amazon’s petition to the Tax Court, in Section 3.3(b) of its amendment to its CSA, Amazon and Amazon Europe reserved the right to adjust the cost sharing payments attributable to the inclusion of stock-based compensation in the event that Treasury’s 2003 CSA regulations were later held to be invalid by a court’s final decision [15].

Amazon’s cost accounting system during 2005–2006 did not specifically segregate IDCs from other operating costs [16]. Amazon therefore developed a formula and applied it to allocate to IDCs a portion of the costs accumulated in various “cost centers” under its method of accounting. “Cost centers” are accounting classifications that enable petitioner to manage and measure operating expenses. Amazon tracked expenses in six broad categories:

- Cost of Sales;

- Fulfillment;

- Marketing;

- Technology and Content (T&C);

- General and Administrative (G&A); and

- Other.

According to Amazon’s 2005 SEC Form 10-K, the T&C category expenses “consist principally of payroll and related expenses for employees involved in research and development, including application development, editorial content, merchandising selection, systems and telecommunications support, and costs associated with the systems and telecommunications infrastructure.” Each of the six broad expense categories, including the T&C category, is a “rollup” of numerous individual cost centers [17]. For some calendar quarters, more than 200 individual cost centers, each recording a specific type of expense, “rolled up” into intermediate cost centers and ultimately into the T&C category. For example, cost center 7710, “Systems and Network Engineering,” rolls up into C210 (“Product Development”) and C250 (“Technology/External”). All costs accumulated in “Product Development” and “Technology/External” roll up into the Technology & Content category.

Through the end of 2011, according to Amazon’s petition, AEHT incurred research and experimental expenses in excess of $1.1 billion under the cost sharing arrangement, which allowed it a nonexclusive right and license to the covered intangibles. AEHT also made up-front buy-in payments to Amazon over seven years, starting in 2005, in consideration for the license and assignment of rights to Amazon’s preexisting technology and marketing intangible property under the cost sharing arrangement. To determine the buy-in, Amazon chose the comparable uncontrolled transaction method (CUT), from which it determined that on January 1, 2005 the preexisting intangibles were worth $216.7 million [18]. Amazon’s buy-in payments totaled $254.5 million [19].

The IRS audit of Amazon’s cost sharing arrangement began in 2008, and in 2009 the IRS hired the company Horst Frisch. On January 14, 2011, Horst Frisch issued a report titled the “Arm’s Length Payments for IP Involved in The Transfer of Amazon’s EU Website Business: Final Report” (Horst Frisch Report). Horst Frisch applied the discounted cash flow method to determine the preexisting intangibles’ value. According to Amazon’s complaint, Horst Frisch relied on an estimate of future cash flows, the timing of the cash flows, and a discount rate of 18 percent to calculate the present value of the projected cash flow—and thus determined the value of the preexisting intangible property at $3.6 billion. The discounted cash flow was based on the projected profits of the European websites between the years 2005 to 2011 with an annual growth rate of 3.8 percent [20].

Amazon.com Inc. received a deficiency notice from the IRS on November 9, 2012 in which the IRS disagreed with Amazon.com’s transfer of intangible property to the AEHT. The IRS, based on its commissioned Horst Frisch Report, valued the preexisting intangibles pursuant to the discounted cash-flow (DCF) methodology to the expected cash flows from the European business. Based on this Horst Frisch Report, the IRS initially issued an adjustment for an additional $3.6 billion but eventually reduced the adjustment to $3.468 billion. In addition to the buy-in adjustment, the IRS made three further adjustments.

- Reallocated income, by reducing deductions that led to an increase in taxable income of $23 million for 2005 and $109.9 million for 2006, to reflect amounts it said Amazon should have received under its cost sharing arrangement effective January 1, 2005.

- Rejected a claim that reflected $9.5 million in reductions in other cost sharing payments for 2005–06 related to the exclusion of stock-based compensation from the intangible development costs subject to the cost sharing arrangement [21].

- Recalculated buy-in allocations, based upon an unspecified method, related to the transfer to AEHT of intangible property from each of Amazon’s acquisitions of Booksurge LLC, Customflix Labs Inc., Pulver Technologies Inc., and Mobipocket.com SA. The resultant adjustment increased for 2005–2006 taxable income by $7.3 million [22].

According to documents filed on July 26, 2013, Amazon.com sought a protective order that would prevent public disclosure of its “trade secrets, intellectual property, or other proprietary and confidential information” [23]. According to the joint status report filed on November 1, 2013, Amazon.com and the IRS agreed to a limited protective order that preserved the confidentiality of Amazon’s customer information and key business data during the pretrial phase of the litigation. Under the terms of the protective order, many of the documents filed during pretrial phase are under seal.

The parties filed the first stipulation of facts and exhibits December 19, 2013. Amazon filed for a partial summary judgment that the Tax Court find the IRS abused its discretion when it treated 100 percent of the technology and content (T&C) costs as intangible development costs (IDCs). On July 28, 2014, the Tax Court denied Amazon’s motion for partial summary judgment, stating:[24]

Petitioner has yet to demonstrate that the T&C category contains nontrivial costs that are properly characterized as something other than IDCs. Respondent has sought discovery on this issue and was seeking additional discovery at the time this motion was filed. At the moment, therefore, it is a disputed question of material fact whether the T&C category contains “mixed” costs. Until petitioner establishes that the T&C category contains a nontrivial amount of “mixed” costs, we cannot rule as to whether respondent abused his discretion in determining that 100% of T&C category costs constitute IDCs.

On December 10, 2014, the U.S. Tax Court granted Amazon’s motion to quash subpoena of Amazon’s CEO, Mr. Bezos. When seeking testimony of CEOs and other high-level corporate officers, courts have required that the requesting party show “that the executive possesses unique knowledge of relevant facts and that the information sought cannot be obtained by less burdensome means.” In the case at hand, the court acknowledges that 21 Amazon fact witnesses had testified and six of those witnesses were S-Team members who reported directly to Mr. Bezos. These witnesses were familiar with all 15 subjects about which respondent proposed to question Mr. Bezos. One of the cases quoted by the opinion, Aminii Innovation Corp. v. McFerran Home Furnishings, states that preparing for and delivering trial testimony is always a burden. The court found that the required testimony would impose an undue burden upon Mr. Bezos and thus granted the petitioner’s motion to quash subpoena.

The tax court trial was conducted under a protective order and concluded Dec. 24, 2014. Upon the conclusion of the trial, the presiding judge commented he would not accept the IRS expert’s testimony supporting the IRS’ position regarding Amazon’s IDC. In 2016, the British newspaper Guardian News & Media LLC filed a motion seeking the release of 16 documents that are in the public record but remain under seal.

About me: Prof. William Byrnes (Texas A&M) is the primary author of a 2,500 page treatise on Transfer Pricing that he updates annually for multinationals to cope with the U.S. transfer pricing rules and procedures, taking into account the international norms established by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It is also designed for use by tax administrators, tax judges, and tax professionals. Fifty co-authors contribute subject matter expertise on technical issues faced by tax and risk management counsel. Free download of chapter 2 here

[1] Amazon.Com, Inc. v. Comm’r, 148 T.C. No. 8, Docket No. 31197-12, (March 23, 2017). Available at https://www.ustaxcourt.gov/UstcInOp/OpinionViewer.aspx?ID=11148 (accessed March 23, 2017). (Hereafter Amazon.com Inc. (2017)).

[2] Veritas Software Corp. v. Commissioner, 133 T.C. 297 (2009).

[3] Xilinx v. Comm’r, 598 F.3d 1191 (9th Cir. 2010).

[4] Altera v. Comm’r, 145 T.C. No. 3, Docket Nos. 6253-12, 9963-12 (July 27, 2015).

[5] Medtronic v. Comm’r, T.C. Memo. 2016-112, Docket No. 6944-11 (June 9, 2016).

[6] Veritas Software Corp. v. Commissioner, 133 T.C. 297 (2009).

[7] Amazon.com Inc. (2016) at 84.

[8] Amazon.com Inc. (2017)) at 84 referring to Sec. 1.482-1(f)(2)(ii)(A).

[9] IRS AOD 2010-05 (December 6, 2010). Available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-aod/aod201005.pdf (accessed March 23, 2017).

[10] IRS AOD 2010-03 (July 28, 2010). Available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-aod/aod201003.pdf (accessed March 23, 2017).

[11] Motor Vehicles Manufacturers Association v. State Farm, 463 U.S. 29 (1983).

[12] CSA-Audit Checklist is available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/tierisec482.pdf (accessed March 23, 2017).

[13] Amazon’s U.S. Tax Court Petition Challenging Buy-In Valuation for 2005–06 Dkt No 31197-12 (Dec 28, 2012). (Hereafter Amazon Petition)

[14] Amazon Petition.

[15] See Section 3.3(b) of the Amendment to the Amended and Restated Agreement to Share Costs and Risks of Intangible Development referring to Treas. Reg. §1.482-7(d)(2) (2003).

[16] Amazon.Com v. Comm’r, T.C. Memo 2014-149, Docket No. 31197-12 (July 28, 2014). Available at http://www.ustaxcourt.gov/InOpHistoric/amazon.com,inc.memo.lauber.TCM.WPD.pdf (accessed March 23, 2017). (Hereafter Amazon.com Inc. (2014)).

[17] Amazon.com Inc. (2014)

[18] Amazon Petition.

[19] Amazon.com Inc. (2016) at 1.

[20] Amazon.com Inc. (2016) at 74.

[21] The Tax Court en banc rejected this approach by the IRS in Altera Corp. V. Commr., T.C. No.s 6253-12 and 9963 -12 (July 27, 2015). The IRS has appealed thiss decision.

[22] IRS Acquisition Buy-In Report referring to Treas. Reg. § 1.482-4(d) (1994).

[23] Amazon.com Inc. (2014).

[24] Amazon.com Inc. (2014).

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer International Tax Blog, please subscribe here.