In many European countries, the question of legal personality has relevance for determining the transparent character of a business entity for tax purposes and this assessment is even more complex when the entity has been established under foreign law. On the other side, in the United States, any business entity can acquire status of corporation according to federal tax classification rules. In the United States, the fiction of legal personality prevails only as a matter of state company law and this regulatory choice seems to create confusion among the European tax authorities.

A) Hybridity without tax planning

Lately, due to the recent OECD movement against double non-taxation and classifications fomenting homeless income, the word “hybrid” has been charged with a negative connotation. However the use of a hybrid does not constitute per default a form of aggressive tax avoidance. Hybridity may occur in the absence of tax planning, just because some jurisdictions use “legal personality” as a crucial criterion for determining the opacity of a business entity, while other jurisdictions do not attach any importance to it. The U.S. federal law applies a three-step test for determining the existence of a separate legal entity:

- Is the arrangement a contract or an entity?

- If it is an entity, is it a business entity?

- If it is a business entity, is it an opaque entity?

The company laws of Sweden, Norway and Finland do not provide for the establishment of any other limited liability companies than the common corporations. In my view, the lack of a correspondent may lead to difficulties in assessing the transparent character of a foreign business entity for tax purposes. In a recent post, I have discussed the case of a business entity created under the U.S. federal law and revealed the importance of the condition of resembling a Swedish corporation for Swedish tax purposes.

B) United States and its renowned check-the-box regulations

In the United States each state has its own company law and the applicable tax principles defining the nature of a business entity may differ from the federal tax definitions. From a European position, it is important to know whether the state or the federal principles will be scrutinised by the relevant tax authorities in Europe in order to determine the transparent character of an entity for tax purposes.

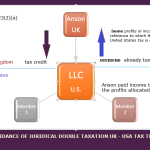

An LLC is a legal person, an entity created under the company law of a state. It resembles to a certain extent some European business entities: Ltd (UK and Ireland), Sarl (France, Luxembourg and Switzerland), GmbH (Germany, Austria and Liechtenstein), SUP (EU), S.R.L. (Italia, Romania and Spain), ApS (Denmark) and ehf (Iceland). An LLC may be treated according to U.S. federal law:

- By explicit choice, as a corporation (C or S corporation),

- By default, if more than two members, as a partnership, or

- If the business entity is an SMLLC, as part of the owner’s tax return (disregarded entity).

An LLC with at least two members is typically treated as a partnership, while an SMLLC (single member LLC similar with the European SUP) will be deemed to constitute a disregarded entity. If the LLC elects to be treated as a corporation, it shall file a special form “Entity Classification Election”. There are two forms: 2553 for an S corporation (SME & self-employed) and 8832 for a C corporation (large companies). Only C corporations are fiscally opaque entities, S-corporations are flow-through entities, exactly as a partnership.

However an S-corporation cannot have shareholders, who neither are U.S. citizens nor are domiciled in the United States. Hence, the major advantages implied by the form S corporation will not be available for an LLC with foreign members. These advantages are the following:

- Unlike a C-corporation, it is not subject to economic double taxation;

- Unlike a usual LLC (partnership), the distributions of an S-corporation (dividends) are not subject to employment taxation.

A non-resident – either legal or natural person – can own an SMLLC in the United States. If an SMLLC is owned by a corporation, its fiscal situation should be reflected on its owner’s federal tax return as a division i.e. a branch of the foreign company. By filing a form, the single member can request that the SMLLC shall be treated as a C corporation for federal tax purposes.

C) Getting lost in translation in a discussion about empty legal forms

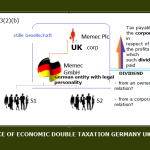

When classifying an LLC for UK tax purposes, HMRC applies the approach of the Court of Appeal in Memec and the preceding line of relevant case law. In practice, this inquiry requires to formulate an answer to a set of questions.

- a) Does the foreign entity have a legal existence separate from that of the persons who have an interest in it?

- b) Does the entity issue share capital or something else, which serves the same function as share capital?

- c) Is the business carried on by the entity itself or jointly by the persons who have an interest in it that is separate and distinct from the entity?

- d) Are the persons who have an interest in the entity entitled to share in its profits as they arise; or does the amount of profits to which they are entitled depend on a decision of the entity or its members, after the period in which the profits have arisen, to make a distribution of its profits.

- e) Who is responsible for debts incurred as a result of the carrying on of the business: the entity or the persons who have an interest in it?

- f) Do the assets used for carrying on the business belong beneficially to the entity or to the persons who have an interest in it?

In a recent ruling, Anson v CIR, the UK Supreme Court decided that the members of a particular LLC had a “direct” interest in the profits of the LLC, thus this business entity has been found to be fiscally transparent. (By comparison, for U.S. tax law purposes, full transparency implies that all gains and losses of the LLC shall be passed through to Mr Anson on a current basis).

“The profits do not belong to the LLC in the first instance and then become the property of the members. … Accordingly, our finding of fact in the light of the terms of the LLC operating agreement and the views of the experts is that the members of [the LLC] have an interest in the profits of [the LLC] as they arise”.

The Court’s decision in Anson does neither scrutinize the tax effects of an SMLLC nor of a Delaware LLC that has filed a tax election to be treated as a C corporation for U.S. federal tax purposes, but could such conclusions be extrapolated from this ruling? The lack of clarity and the alembicated manner in which the Court provides its conclusions in Anson brings about a limited value as a precedent.

The question whether “the persons who have an interest in the entity were entitled to share in its profits as they arise” appears to be the main criterion used by UK courts for determining the existence of a separate entity for fiscal purposes. In the meanwhile, the LLC in Anson could be deemed as transparent – in the sense employed by the UK courts – simply because it does not issue shares or other comparable titles and the same is true about the German GmbH.

The key issue in my view pointed out as well by the different choice of relevant law in Memec compared with Anson is the fact that the legal question requiring an answer differs fundamentally. In Memec the Court aims to establish the identity of the person taxpayer, while in Anson the main issue is the identity of the source of income reflected by the expression “UK tax computed by reference to the same income as was taxed in the US”. Looking back to the Swedish case discussed previously, the pertinent question would be closer to Anson’s, since the income becomes liable to tax under Swedish law, only to the extent that it is remitted to Sweden and this remittance occurs according to rules imposed by the U.S. federal tax regulations.

The absence of share capital (capital stock) is the main reason why the persons must have a direct interest in the profits of the entity. In any case, the use of legal personality as paramount criterion of fiscal transparency should be looked over. The test of legal personality may indicate the presence of an entity, but it has nothing to say about its opacity for tax purposes. The endeavour to examine the company law of the U.S. state in order to determine whether the definition of limited liability or legal personality is similar with the definition in the country where the owner resides resembles in any case Sisyphus’ plight. An obviously much more appropriate solution would be to study the conditions imposed by the U.S. federal tax regulations for each type of business entity.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer International Tax Blog, please subscribe here.