As from the first BEPS proposals with respect to intangibles, it has been considered that the Arm’s Length Standard (“ALS”) is “slowly but surely being relegated to the back seat” of the OECD Guidelines.[1. R. Robillard, BEPS: Is the OECD Now at the Gates of Global Formulary Apportionment?, 43 Intertax 447, at 447.] Indeed, some approaches contended in the OECD “Guidance on Transfer Pricing Aspects of Intangibles”[2. OECD (2014), Guidance on Transfer Pricing Aspects of Intangibles, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing.] cannot be explained under the ALS. The effects of such statement cannot be minimized. These approaches suggested by the OECD Guidelines are actually in breach of the treaties to which the Guidelines are intended to apply.

The ownership of intangibles is central to the creation of MNEs. Intangibles are assets that cannot be easily replaced and must be protected against opportunistic behavior, since they demand large investments from MNEs upon their production. Fixing an ALS price of an intangible asset among the entities of an MNE may be deemed to be essentially a feasibility issue, allowing a great divergence on valuation methods. There is a perception that MNEs may be using intangibles as means to shift income to tax heavens, what cannot be precisely determined or evidenced, exactly due to the lack of consensus as to determine an ALS valuation of these assets. Curiously enough, while one would expect this issue to be faced by means of pragmatic approaches which would try to harmonize the 50-year experience on ALS (and the existence of more than 3,000 tax treaties in force providing for such standard), the present discussions are based on alternatives that cannot be explained under the ALS. More dramatically, the intent to combat BEPS has led to suggestions that, if adopted, will completely jeopardize the allocation of income, when applied to situations where the economic group rightfully intends to keep the asset under the legal ownership of a subsidiary that has not performed functions or contributed with assets or other factors that, from a BEPS perspective, engender the creation of value. These solutions are intended to address situations in which “(i) intangibles are self-developed by a multinational group, especially when such intangibles are transferred between associated enterprises while still under development; (ii) acquired or self-developed intangibles serve as a platform for further development; or (iii) other aspects, such as marketing or manufacturing are particularly important to value creation.”

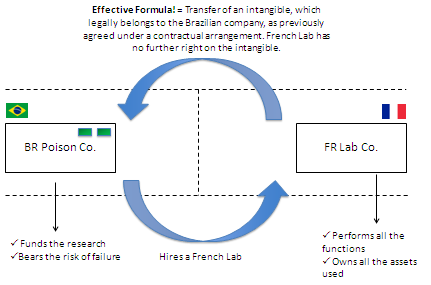

One may imagine the example of a Brazilian independent company performing the extraction of poison from snakes, for the sole purpose of producing the respective serum, to supply Brazilian and Bolivian hospitals with such remedy. This example is suggested because one can reasonably assume that such serum is market-oriented, i.e., snakes found in South American forests are not found in other parts of the world and the serum is produced from the poison of the snake which effects the serum is supposed to combat. Under this scenario, one could consider the case in which the Brazilian company would decide to invest on research for substances able to stimulate the production of poison by the snakes, due to an increase of demand in the local market (which is, perhaps, the sole market for such product). For this purpose, as the company would not able to perform the research by itself, it could decide to hire a French laboratory, which would perform all the functions and provide for all the assets related to the research. The Brazilian company would solely fund the research, assuming, on the other hand, the risks related to the failure of the research. By the end of the research, the French company would reach an effective formula, whose rights would all legally belong to the Brazilian company, as previously agreed under a contractual arrangement. According to the ownership clause in the agreement, the French company would not be entitled to any right derived from the exploitation of the intangible produced.

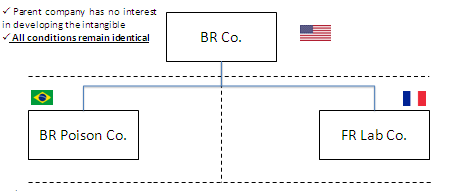

Consider now a similar situation, but this time between parties under common control. In the very same example, if the Brazilian company were the subsidiary of a US-based MNE, it could be possible that the group as a whole would have no interest in developing the referred intangible. Accordingly, as already mentioned above, the serum would be aimed at poison of South American snakes, thus having no worldwide application. In such case, the only option for the subsidiary would be to fund the referred research with its own resources. Within this intent, the company could choose to hire another subsidiary of the group, under the very same conditions described in the uncontrolled example, leading to an ownership of an intangible to the Brazilian subsidiary, in the same conditions as in the previous example.

How would these controlled transactions be treated for transfer pricing purposes? Under the ALS, the French subsidiary should be remunerated equally in both examples, if the transactions concerned are identical. However, when applying the approach suggested by the OECD “Guidance on Transfer Pricing Aspects of Intangibles”, there are reasons to believe that the taxation of the transaction could be distinct in each case.

The report puts into perspective the legal ownership of intangibles, taking it as a mere “starting point for any transfer pricing analysis of transactions involving intangibles”.[3. OECD (2014), Guidance on Transfer Pricing Aspects of Intangibles, at 40, para 6.35.] According to the proposal, “legal ownership of intangibles, by itself, does not confer any right ultimately to retain returns derived by the MNE group from exploiting the intangible”[4. OECD (2014), Guidance on Transfer Pricing Aspects of Intangibles, pp. 41-42, para 6.42.] The OECD suggests that “[t]he return ultimately retained by or attributed to the legal owner depends upon the functions it performs, the assets it uses, and the risks it assumes, and upon the contributions made by other MNE group members through their functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed”. The report even gives the example of an internally developed intangible where the legal owner performs no functions, uses no assets and bears no risks, case in which it will not be entitled to “any portion of the return derived by the MNE group from the exploitation of the intangible other than arm’s length compensation, if any, for holding title”.[5. OECD (2014), Guidance on Transfer Pricing Aspects of Intangibles, pp. 41-42, para 6.42.]

In the example described, the application of the approach suggested in the OECD “Guidance on Transfer Pricing Aspects of Intangibles” implies that, for transfer pricing purposes, the Brazilian company should not be entitled to the total of rents derived from the exploitation of the intangible. Paragraph 6.47 considers that:

As stated above, a determination that a particular group member is the legal owner of intangibles does not, in and of itself, imply that the member has the right ultimately to retain or have attributed to it the receipts that may accrue in the first instance to that member as a result of its commercial right to exploit the intangible, nor does it necessarily imply that the legal owner is entitled to any income of the business after compensating other members of the MNE group for their contributions in the form of functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed. That is, after appropriately rewarding other members of the MNE group for their functions performed, for assets used, and for risks assumed, the income of the legal owner related to the intangible may be positive, negative or zero depending on the facts of the case.[6. OECD (2014), Guidance on Transfer Pricing Aspects of Intangibles, at 43, para 6.47.]

Hence, even if, as in the given example, the Brazilian company adequately remunerates the French companies for the activities performed and assets used, it may be the case that the Brazilian company will not be entitled to benefit from the total of rents derived in the exploitation of the intangible. As it is drafted, paragraph 6.47 leads to the conclusion that the Brazilian entity shall remunerate ad eternum the French company for the functions performed, assets used and, eventually, for the risks assumed by the French subsidiary. The report is permeated by statements that imply that the Brazilian company will never be free from the contract it signed with the French subsidiary, and a remuneration for the exploitation of the intangible shall always be paid.[7. See, for example, para 6.63, according to which: “(t)he identity of the member or members of the group bearing and controlling risks related to the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection, and exploitation of intangibles is also an important consideration in determining prices for controlled transactions and in determining which entity or entities will be entitled to share in returns derived from the exploitation of the intangibles”.]

It is not an exaggeration to consider that, in fact, the report forbids an ALS approach, as

“[t]he need to ensure that all members of the MNE group are appropriately compensated for the functions they perform implies that if the legal owner of intangibles is to be entitled ultimately to retain all of the returns derived from exploitation of the intangibles it must perform all of the functions, contribute all assets used and assume all risks related to the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation of the intangible”.

In other words, if the entity wishes to keep all the rents derived in the future exploitation of the intangible, it must do everything alone. Otherwise, it will always owe something to its related parties.

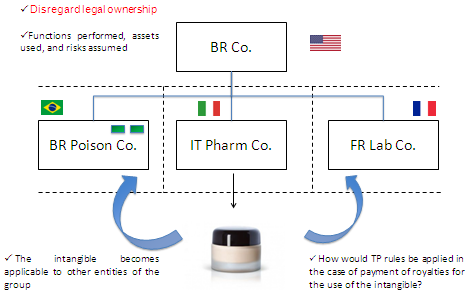

The BEPS proposal also risks to create uncertainty with respect to “unanticipated ex post returns”. In the given example, one may imagine an event where a third party, not related to the MNE, discovers an extremely successful cosmetic application for the poison of the snake. Hence, while, in principle, the intangible developed was of restrict use, solely relevant for the Brazilian and Bolivian local market, this situation changes and an Italian subsidiary of the MNE decides to engage in the production of the cosmetic.

It may sound obvious that the Brazilian subsidiary will be extremely benefited from the supervening event, as the Italian subsidiary will be interested in paying for the outcomes of the intangible produced, and the Brazilian company is the legal owner of the intangible, since it has funded the development of the asset at arm’s length. However, some statements of the proposal demand a second look on the issue. As per the OECD proposal, the entities benefiting from these unanticipated ex posts returns “may or may not be the legal owner of the intangible, and may or may not be the entity or entities providing funding for the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection, or exploitation of the intangible”.[8. OECD (2014), Guidance on Transfer Pricing Aspects of Intangibles, at 50, para 6.67.]

This example seems enough to demonstrate that BEPS initiative may be deviating from ALS. This is extremely dangerous, if one considers that this standard is present in almost all treaties in force. One can expect the OECD to be aware of this fact and this explains the reason why the OECD does not clearly declare that the ALS shall not be applied to intangibles. This would be a honest approach, but would certainly not be a practical solution, unless all countries would agree in changing their tax treaties in order to admit an exception to the existing rules present in Article 9 of OECD-MC. The OECD itself does not seem to believe that this consensus could be reached, and therefore the BEPS Action 14 (Multilateral Agreement) does not dare to touch this problem. In face of such circumstance, the OECD found no alternative, other than extending the interpretation of Article 9 (and therefore of the ALS). This would not be the first time in which the OECD, in face of a concrete problem of its Model, decides to change its commentary, under the excuse of mere clarification. Such extensions are hardly acceptable under international law, especially when one takes into account that the OECD claims that modifications of the commentaries should be applied retroactively, under the dynamic approach. One can certainly agree that ALS allows a broad range of valid interpretations, what can be seen by the variety of national transfer pricing rules, all of them claiming to comply with this standard. However, as the example above shows, the BEPS initiative on intangibles seems to go too far and its suggestions have left the ALS aside. No dynamic interpretation can be accepted when a modification in the core of a treaty rule is suggested.

The problem of intangibles, as already mentioned, cannot be quantified. What is real is that MNEs presently have profits in jurisdictions where no significant function is performed and no presence in market justifies such results. If this is the problem, one can ask why not to face this specific problem – allocation of profits to low tax jurisdictions – instead of disrespecting all tax treaties in force. It is true that the definition of a low tax jurisdiction is not easy, and several countries, including OECD Member States, have special tax regimes which would attract profits to be deviated thereto. However, this is an issue which can be solved through other actions (Action 6). For instance, Brazil and Portugal renegotiated their tax treaty to exclude from its benefits the Madeira zone, due to the tax regime available therein. Exclusion of benefits and more strict deduction rules for payments to companies under special regimes (even indeductibility) could be a remedy strong enough to combat BEPS through intangibles. The present OECD goes much further, and together with valid BEPS concerns, reaches millions of non tax driven transactions within MNEs, which certainly violates the principle of proportionality, and moreover creates uncertainty for legitimate transactions as well.

In any case, it is clear that the solution presented by the BEPS proposal cannot be derived from a correct application of the ALS and can therefore hardly be justified under the principle of equality. As to address a very specific issue (i.e., the use of low tax jurisdictions in the allocation of intangibles), the BEPS solution jeopardizes the entire transfer pricing system. If the proposal, upon delivering large discretion to tax authorities, “may or may not” lead to a fair allocation of tax revenues, one thing is certain: the proposal is surely in breach of the OECD Model Convention.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer International Tax Blog, please subscribe here.

Kluwer International Tax Law

The 2022 Future Ready Lawyer survey showed that 78% of lawyers think that the emphasis for 2023 needs to be on improved efficiency and productivity. Kluwer International Tax Law is an intuitive research platform for Tax Professionals leveraging Wolters Kluwer’s top international content and practical tools to provide answers. You can easily access the tool from every preferred location. Are you, as a Tax professional, ready for the future?

Learn how Kluwer International Tax Law can support you.